Since 1993, FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program has funded the acquisition of over 55,000 flood-damaged properties. Under FEMA’s acquisition programs, once properties are purchased following a disaster, existing structures must be removed and the land must be dedicated to open space, recreational, or wetland management uses. These properties can offer opportunities to restore and permanently protect natural habitats and help conserve biodiversity, while also providing community amenities and improving resilience.

Local governments usually oversee floodplain buyouts, and ultimately take on the ownership of these sites, with little or no funding for restoration or management, or guidance on maximizing long-term benefits. As a result, many acquired properties remain fallow, underutilized, empty lots – and communities thus often miss the opportunity to leverage the potential benefits of these properties.

However, communities across the country have established programmatic and management structures for floodplain buyouts that have attempted to make the most of acquired properties. We have developed practical, implementable recommendations for how communities across the country can optimize use and management of buyout properties to provide habitat and improve community resilience. There are many opportunities for organizations or agencies interested in conservation or wetland restoration to be valuable partners for local governments in the floodplain buyout process.

More information about floodplain buyouts:

- What are Floodplain Buyouts?

-

Floodplain buyouts, or the voluntary acquisition of flood-damaged property, are intended to mitigate flood damage by moving people and structures out of harm’s way. Buyouts can be completed under federal, state, and sometimes local programs, but the largest source of funding is FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP). In 1993, the Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, or Stafford Act, was amended to create the HMGP, as a response to a series of disasters that cost numerous lives and caused $15-20 billion in damage. The 1993 amendment authorized funding for various programs, including the HMGP, intended to reduce and eliminate, where possible, long-term risk of flood damage for structures insured by the National Flood Insurance Fund (NFIF), with the ultimate aim of reducing the number of claims paid by the NFIF. Projects eligible for HMGP funding include flood-proofing, elevation, reconstruction and retrofitting projects, but one of the HMGP’s key roles is to provide funds for local governments to acquire flood-prone properties, or floodplain buyouts.

- How does FEMA'S Hazard Mitigation Grant Program work?

-

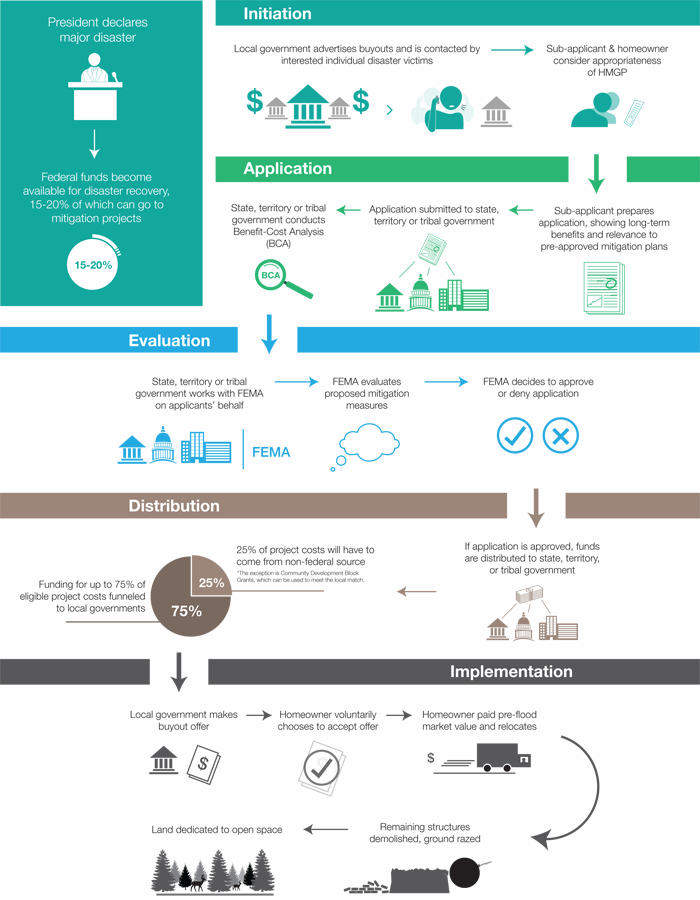

The President of the U.S. must declare a “major disaster” within the jurisdiction of a state, territory, or tribal government in order to activate federal funds held in reserve for disaster assistance and mitigation, including Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) funds. Following the disaster declaration, local governments, or sub-applicants, work with state agencies (applicants) to apply for funds for cost-beneficial acquisitions of property from willing landowners. The graphic below highlights key phases and steps in completing a floodplain buyout with HMGP funds:

Learn more from the Action Guide or FEMA's HMGP website.

- How many HMGP-funded buyouts are there? Where are they?

-

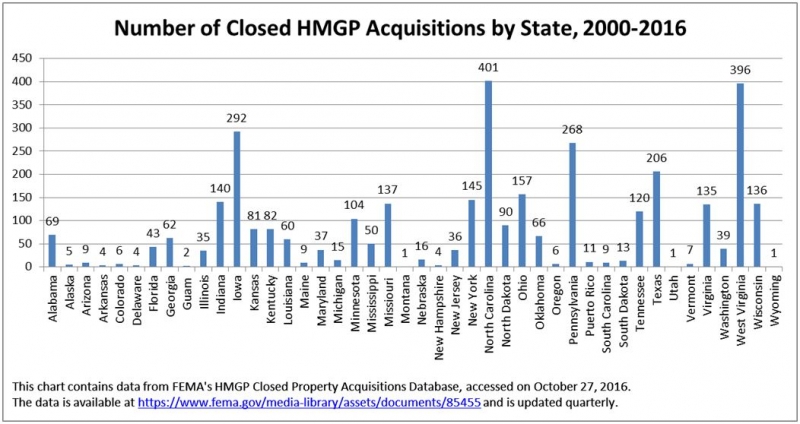

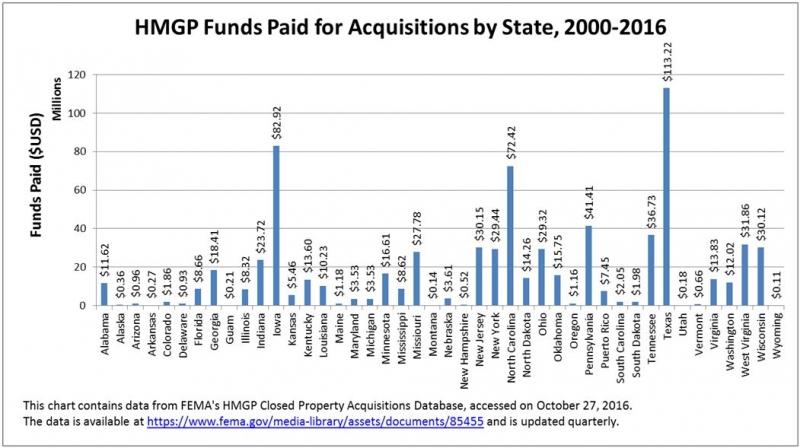

Over 38,000 properties have been acquired with HMGP grants since 1993, many of which are related to flood hazard mitigation. Between 2000 and October of 2016, HMGP funds were used to close 3500 acquisitions. The majority are in North Carolina, West Virginia, Iowa, and Pennsylvania. The graphs below show the number of HMGP-acquired properties and HMGP funds distributed by state, 2000-2016:

The University of North Carolina Institute for the Environment and the Environmental Law Institute chose to conduct representative case studies in Minnesota, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Wisconsin.

- What happens after properties are acquired?

-

Once structures are removed and the land is graded, acquired properties must be dedicated to “open space.” Deed restrictions that effectively mitigate future risk of structural damage must be attached to the property title. These restrictions delineate uses of the property compatible with “open space” requirements and may forbid the construction of certain structures. See FEMA’s model deed restriction.

Local governments typically take control of the property and either leave it as an empty lot or use it for some pre-approved project, such as a park or trail connection. Conservation easements, title transfers, and leases may enable other approved entities to take responsibility for subsequent projects, such as community gardens or habitat restoration.

The feasibility of the various allowable uses of acquired properties depends on various factors such as funding, expertise and community needs, but primarily on the structure or layout of the buyout (e.g. whether the acquired properties are contiguous or dispersed).

- Key Steps for Making Informed Decisions and Taking Action

-

We have devised an action framework for local governments interested in making the most of floodplain buyouts.

Step 1: Gather information. When developing floodplain buyout projects, project leaders should gather information on local natural resources and features, cultural resources and features, areas adjacent to the acquisition site, existing and planned community amenities, and the legal and regulatory landscape. This information may be important for project and permit applications and will help project proponents define achievable goals to produce favorable outcomes.

Gathering information can be facilitated by project proponents or by partnering with government entities or other organizations with expertise in and responsibility for relevant topics.

Step 2: Consider the site in relation to surrounding land uses. Mapping the potential project site helps visualize where parcels are situated in relation to other buyout projects, habitat areas, and existing conversation or protected areas. Maps may also reveal opportunities for connecting habitat areas, identifying partners, and selecting the type of project that would maximize community benefits.

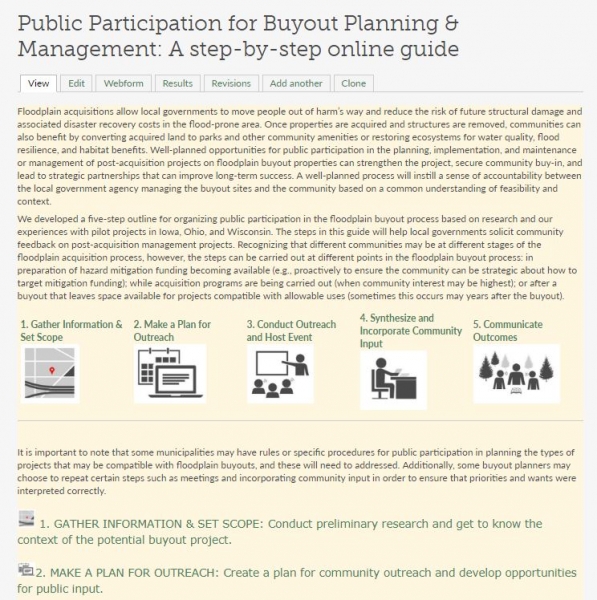

Step 3: Get community input. Community input is important for determining potential uses of acquired properties that will be feasible, fundable, sustainable, and valued by citizens. Workshops or meetings can be used to provide, exchange, and discuss information about the site and potential projects. Ongoing communication beyond the planning stages can help avoid surprises and promote buy-in from neighbors and important stakeholders.

Step 4: Develop goals and objectives. Goals should be defined and attainable and objectives should be well-articulated. Creating a conceptual plan will help articulate ideal options for management and use and should be used to consider various scenarios. Community input is crucial for this step.

Step 5: Finalize and implement the plan for the site’s new use. Finalize a development plan that includes a plan for long-term monitoring and maintenance, considers players involved, includes a realistic budget, and articulates a plan for continual outreach. This will ensure that progress is consistent with goals and objectives.

Our Action Guide details issues to consider when determining what can be done with a property. Challenges include securing funding, ensuring community participation and neighbor buy-in, finding the right partners, working through the permitting process, and defining responsibility for ongoing maintenance and management of an acquired property. The Action Guide also offers insights and recommendations for how to address these challenges drawn from interviews, case studies, and a review of resources related to habitat benefits and community resilience.

Our resources:

You can find ELI and UNC-IE's case studies on communities that have completed floodplain buyout projects here.

ELI and UNC-IE created an action guide for local governments interested in making the most of floodplain buyout projects. You can find our action guide here.

Our handbook about strategic partnerships in the floodplain buyout process can be found here.

Visit our step-by-step online guide for public participation in buyout planning and management here.

Our strategic planning & prioritization guide can be found here.

You can access our guide to financing and incentivizing floodplain buyouts here.

On May 15, 2017, we hosted a webinar on "Making the Most of Floodplain Buyouts." You can view the recording here:

You can also view the PowerPoint from this webinar.

On April 13, 2017, we co-hosted a symposium with the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School on "Using Green Infrastructure for Climate Change Adaptation and Hazard Mitigation." You can view the recording here:

You can also view the PowerPoint from this symposium.

Our Blog Posts

Floodplain Buyouts for the Future (March 27, 2017)

Floodplain Buyouts: From the Archives and for the Future (April 24, 2017)