ELI Report

ELI helps U.S. efforts to address plastic pollution via coherent, comprehensive study of existing federal legal authorities

There is growing momentum in the United States and at a global level to address the problem of plastic pollution. ELI, in partnership with the Monterey Bay Aquarium, helped the conversation take a big step forward by identifying existing legal authorities to attack the externalities of this ubiquitous and useful material.

In March, ELI published <Existing U.S. Federal Authorities to Address Plastic Pollution: A Synopsis for Decision Makers. This report identifies legal means for the federal government to leverage in achieving the national goal of eliminating plastic released into the environment by 2040. Building on the legal framework established by a congressionally mandated report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, the ELI report categorizes federal authorities—spanning executive orders, legislation, regulations, and associated programs—into specific “intervention areas” across the plastic life cycle.

The report arrays these intervention areas alongside relevant authorities and their implementing agencies. Through discussions of each authority’s text and traditional application, the report describes how the federal government’s existing authorities can address plastic pollution across various stages of the plastic life cycle. ELI and MBA presented the conclusions of the report at the World Wildlife Fund’s Plastic Policy Summit.

The various intervention areas outlined in the report include reducing plastic production and pollution from production, innovating material and product design, decreasing waste generation, improving waste management, capturing plastic waste from the environment, minimizing at-sea disposal, and supporting information and data collection.

For each of these intervention areas, the report identifies legal authorities and relevant statutes. For example, the report identifies EPA as having authority to reduce plastic production and pollution from production as “Under the Clean Air Act, EPA can consider microplastic as a unique ‘air pollutant.’” The other authorities identified to reduce plastic production and pollution from production include those possessed by the Council on Environmental Quality, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and Food and Drug Administration.

In great detail, the report documents each of the remaining intervention areas and relevant legal authorities, including, but not limited to, Consumer Protection Safety Commission, Department of Energy, Internal Revenue Service, Department of Commerce, and Department of Agriculture.

Notably, major environmental laws are cited as legal pathways, including the Toxic Substances Control Act, Clean Water Act, Coastal Zone Management Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, Clean Air Act, Endangered Species Act, and more.

The report can also be used to conduct a gap analysis to identify specific aspects of addressing plastic pollution on which no existing authorities exist. ELI will continue its partnership with the Monterey Bay Aquarium on this important work.

Preparing for environmental accountability in Ukraine war

Beyond the devastating human toll of the war in Ukraine, the natural environment has also been a significant casualty. There have been chemical releases from damaged industrial sites, the militarization of nuclear sites, destruction of Kakhovka dam and the ensuing flood damage, impacts on air quality from the devastated cities and burned forests, ecological consequences of damage to agricultural areas and natural resources, water pollution and destruction of water infrastructure, pillage of natural resources, and pollution of sensitive terrestrial and marine areas. These impacts extend beyond the borders of Ukraine. Addressing this damage is a critical part of accountability and recovery.

Since convening the First International Conference on the Environmental Consequence of War in 1998, ELI has been a leader in informing the operation of mechanisms for accountability and post-war recovery, particularly with respect to the law, science, and economics of wartime environmental damage. This includes the UN Compensation Commission through which Iraq compensated Kuwait for wartime environmental damage to its oilfields, desert, and marine environment.

In preparation for recovery efforts in Ukraine, ELI is working with its government and other international partners to prepare for accountability and recovery. ELI supported the International Working Group on the Environmental Consequences of War in the development of “An Environmental Compact for Ukraine” and is continuing to advise on the legal, scientific, and economic dimensions of accountability for wartime environmental damage, to facilitate this effort and improve the effectiveness of environmental claims.

Food for thought: ELI’s submissions to EPA on food waste

Earlier this year, ELI submitted comment letters to EPA responding to the agency’s Draft National Strategy for Reducing Food Loss and Waste and Recycling Organics. The Institute proposed updates to EPA’s Waste Reduction Model, known as WARM, a spreadsheet-based tool for analyzing the potential lifecycle emission and energy savings of various waste management practices.

These comments build on the work of ELI’s Food Waste Initiative, which conducts research and works with stakeholders to prevent waste, increase surplus edible food donations, and recycle the remaining scraps.

One comment regarding the Draft National Strategy is summarized on our blog at go.eli.org/qvh.

The remaining two comment letters emphasized the importance of developing the data and tools needed to conduct comprehensive lifecycle greenhouse gas impact assessments for zero-waste strategies of source reduction, reuse, and recycling, particularly for food waste.

ELI points out that climate action planning relies on GHG inventory accounting, in which waste-sector data only capture emissions from product end-of-life to final disposition—for example, shifting from landfill to composting or anaerobic digestion. Yet by one estimate, more than 85 percent of GHG emissions associated with food waste occurs in the supply chain upstream from the landfill.

The ELI comments commend the lifecycle framework of the WARM model: it projects avoided upstream GHG emissions from food waste source reduction and donation, and downstream carbon sequestration gains from land application of recycling food scraps. However, they recommend several model modifications.

These include adding in the impacts from avoided land use change, which is responsible for over half the GHG reductions according to some estimates, and differentiating where in the supply chain from farm to households the food loss or waste is prevented. They further recommend development of improved data identifying the extent of changes in prevention, edible food recovery and recycling attributable to specific policies and programs.

Existing Federal Authorities to Combat Plastics Pollution.

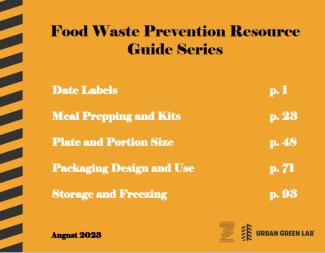

Food Waste Prevention Resource Guide Series

ELI created the Food Waste Prevention Resource Guide Series (funded by Urban Green Lab with support from the Posner Foundation of Pittsburgh) to provide ready-to-use, vetted, and science-based resources for classrooms, households, and workplaces. The Guides provide a range of resources, such as lessons plans and research reports, on specific food waste prevention strategies, including: Date Labels; Packaging Design and Use; Meal Prepping and Kits; Plate and Portion Size; and Storage and Freezing. This PDF compiles all five resource guides into one document.

Policy That Produces Progress: Model Ordinances and Other Governance Tools to Reduce Food Waste

State and City Food Waste Reduction Goals: Context, Best Practices, and Precedents

ELI’s Food Waste Initiative is publishing a Research Brief Series to present takeaways from the Initiative’s research, spanning a range of topics important to food waste prevention, recovery, and recycling. To access other research briefs in the series, visit: https://www.eli.org/food-waste-initiative/publications. State and City Food Waste Reduction Goals: Context, Best Practices, and Precedents reviews the status of food waste reduction goals in the United States.

ELI Report

Research Paper Filling the gaps in state programs to protect Waters of the United States in a post-Sackett world

The wake of May’s Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. EPA, combined with a rule change issued by the agency in August, has shifted the legal protections afforded to Waters of the United States, known commonly as WOTUS, under the federal Clean Water Act. These actions place a substantial burden on state and tribal regulators and legislators to protect waters within their jurisdiction.

In May, ELI published a research paper titled Filling the Gaps: Strategies for States/Tribes for Protection of Non-WOTUS Waters. The study identifies which states are reliant on the federal agency’s definition for protection of freshwater wetlands and tributaries from dredge and fill, which states have limited coverage for non-WOTUS waters, and which states have comprehensive permitting programs applicable to their waters that may fall outside of federal coverage under the act.

The report goes in depth into states with fairly comprehensive permitting programs applicable to their waters (i.e., wetlands) including those that fall outside the coverage of the federal CWA. These are California, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. This section also makes comparisons between states in this category, demonstrating how the coverage of these programs varies.

The study includes a number of states that have adopted specialized laws and regulations, or in some states case-by-case review practices, that are expressly intended to fill identified gaps in federal CWA coverage. These states provide some regulatory protections for identified classes of non-federal waters, including certain of their nontidal wetlands.

Some states provide regulatory authority and funding to specific activities affecting protected waters. The seven states with limited or gap-filling regulatory coverage are: Arizona, Illinois, Indiana, North Carolina, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wyoming, plus the District of Columbia. The report includes a comparative analysis among all of these regulations.

In addition to statewide programs, the report looks at alternative or supplemental approaches that may protect non-WOTUS waters. These approaches include state or local regulations of activities to protect buffer areas adjacent to waters and wetlands; local regulation of wetlands/waters (as authorized by state law or by home rule); regulation of particular activities rather than of specified waters; conservation planning; water quality standards for certain non-WOTUS water; conservation banking with protection for wetlands/waters; voluntary conservation and restoration programs; and hazard mitigation or resilience.

The study also includes an analysis of tribal wetlands programs. The CWA authorizes EPA to treat tribes with reservations as similar to states, allowing these tribes to administer regulatory programs and receive grants under CWA authorities.

Tribes may also develop regulatory programs under tribal law and create non-regulatory programs to protect, manage, and restore wetlands on their lands. More than 40 tribes have submitted independent wetland program plans. Tribal wetland programs, as do state programs, vary widely.

A good deal of investment is needed at the state and local level to ensure that the critical functions provided by wetlands and other waters are not lost.

TSCA conference takes up reducing PFAS in the environment

The Toxic Substances Control Act Annual Conference is hosted by ELI, Bergeson & Campbell, P.C., and the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health. Each year, the conference brings together premiere TSCA experts to reflect on challenges and accomplishments since the implementation of the 2016 Lautenberg Amendments.

This year, Lynn Bergeson and Bob Sussman started off the program with broad reflections on the current state of TSCA implementation. Following that, EPA Assistant Administrator Michal Ilana Freedhoff gave a keynote discussion, announcing the EPA Framework for Addressing New PFAS and New Uses of PFAS.

The first panel discussed various aspects of EPA’s risk evaluation of chemical substances. The panelists covered the agency’s potential use of European Union REACH data, EPA’s use of new approach methodologies, the effectiveness of a “whole chemical approach” to risk determinations, and the incorporation of cumulative risk assessment in TSCA risk evaluation.

The second panel discussed EPA’s authority under the Lautenberg Amendments to manage chemical risks. The discussion included how the agency manages workplace risks, enforcement mechanisms for risk management restrictions, whether EPA’s risk management rulemakings are adequately addressing environmental justice concerns, and potential legal challenges to final risk management rules.

This year’s conference featured five former assistant administrators who oversaw EPA’s toxics office.

The third panel discussed new-chemical review under the 2016 revision of TSCA. Panelists covered transparency, processes to guide new-chemical review, new approaches to assess chemical risks, concerns for workers and fenceline communities, and recent trends with EPA’s review of new-chemical substances.

The final panel discussion covered the unique role of TSCA, as compared to other EPA programs, in addressing the issue of PFAS. Experts discussed the agency’s working definition of PFAS, the effectiveness of TSCA implementation in addressing PFAS, whether PFAS should be regulated on a category or chemical-specific basis, and more.

Speakers included Shari Barash, Lynn Bergeson, Madison Calhoun, Jordan Diamond, Maria Doa, Emily Donovan, Alexandra Dapolito Dunn, Richard E. Engler, David Fisher, Michal Ilana Freedhoff, Eve Garnet, Lynn Goldman, Ben Grumbles, Rashmi Joglekar, Jim Jones, Jonathan Kalmuss-Katz, Matt Klasen, Pamela Miller, Jeffery Morris, W. Caffey Norman, Steve Owens, Steve Risotto, Daniel Rosenberg, Jennifer Sass, Robert Sussman, Brian Symmes, and Meredith Williams.

ELI members can access a recording of the entire TSCA conference and all associated materials as part of their membership on the ELI website.

Nashville signs order on reducing food waste

A new Model Executive Order on Municipal Leadership on Food Waste Reduction developed by the Environmental Law Institute and Natural Resources Defense Council can help localities reduce the amount of food wasted throughout municipal operations, highlight the importance of reducing food waste, and demonstrate food waste reduction measures that businesses and other entities may voluntarily replicate.

The model was developed as part of ELI’s Food Waste Initiative, which aims to help stakeholders meet U.S. food loss and waste goals by implementing public policies and public-private initiatives to prevent food waste, increase surplus food rescue, and expand scrap recycling.

Up to 40 percent of food in the United States is wasted. Local governments are well-positioned to address the problem. Given the large amount of food that some municipalities procure and the many people that they employ, the impact of food waste reduction measures in municipal operations can be substantial.

The model offers a range of municipal measures to reduce food waste that include staff training and hiring, procurement policies, and employee benefits.

Recently, Nashville adopted a resolution in support of two key measures in the model: a food waste reduction goal and adoption of best food waste reduction practices by municipal departments.

Filling the Gaps in State Programs to Protect WOTUS

ELI Report

ELI at the UN Institute advances rule of law, peacebuilding, and ocean conservation at key international conferences last summer

Fifty years after the United Nations’ first global Conference on the Human Environment, world leaders convened in Sweden this past June to take stock of environmental governance achievements and work toward the next era of sustainable development. At this year’s Stockholm+50 conference, ELI played a key role in two official side events and engaged in several other panels to promote environmental peacebuilding and environmental rule of law.

On June 2, ELI partnered with the Environmental Peacebuilding Association, Geneva Peacebuilding Platform, and PeaceNexus to convene an official side event on Improving Sustainable Development by Integrating Peace. The panel was moderated by ELI Senior Attorney Carl Bruch and featured Research Associate Shehla Chowdhury. Speaking to a full house, panelists discussed the connections among peacebuilding, sustainable development, and conservation by highlighting illustrative case studies and initiatives.

On the same day, ELI also co-sponsored an official side event on Judges, the Environmental Rule of Law, and a Healthy Planet Since the 1972 Stockholm Declaration. Participating judges included several long-time partners of ELI, including Justice Antonio Benjamin of Brazil, head of the Global Judicial Institute on the Environment, Justice Brian Preston of New South Wales, Australia, Justice Mansoor Ali-Shah of Pakistan, and Justice Michael Wilson of Hawaii—all leading champions of climate action.

Prior to the official Stockholm+50 conference, the Institute also co-sponsored a two-day Symposium on Judges and the Environment: The Impact of the Stockholm Declaration in Shaping Global Environmental Law and Jurisprudence. At the event, President Emeritus and International Envoy Scott Fulton presented ELI’s Climate Judiciary Project. The program is the only one in the world working to equip judges with the basic climate science education needed to administer justice in climate-related cases. Fulton shared that the project is now looking to pivot internationally, with the goal of sharing the same knowledge base with justices around the world.

Later in the summer, ELI Oceans Program Director Xiao Recio-Blanco and Visiting Attorney Patience Whitten joined the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Portugal, from June 27 to July 1. As part of the summit’s events, ELI hosted the Future of Food Is Blue panel, in partnership with the Environmental Defense Fund, World Wildlife Fund, Rare, the Government of Iceland, and others. The event formally launched the Aquatic Blue Food Coalition, which promotes fish, shellfish, plants, and other aquatic foods to address food security and climate.

Recio-Blanco spoke at a reception immediately following to share ELI’s research on sustainable fisheries, highlighting the Law and Governance Toolkit for Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries, published in 2020. The toolkit helps legal drafters develop effective policy mechanisms to sustainably manage small-scale fisheries.

Advancing migration with dignity through innovative research

Climate change, war, economic insecurity, and a myriad of other global issues have accelerated internal displacement and global migration. Yet migrants typically suffer many indignities during their transition to a new place, and existing institutions often fail to recognize their basic human rights. In response to this challenge, ELI and its partners have undertaken groundbreaking work on Migration With Dignity, a framework that offers legal and policy options for governments, policymakers, and nonprofits to uphold the dignity of migrants. The concept builds upon the policies of former President of Kiribati Anote Tong, who asserted the need for the people of Kiribati to maintain their autonomy and standard of living throughout the migration experience.

A recent special issue of the Journal of Disaster Research reflects a collaboration between ELI and the Dignity Rights Initiative, the Delaware Law School, the UN International Organization for Migration, and the Ocean Policy Research Institute. ELI Senior Attorney Carl Bruch co-authored two articles, Migration With Dignity: A Legal and Policy Framework, and The Methodology and Application of a Migration With Dignity Framework, along with Shanna N. McClain, NASA disasters program manager and former ELI visiting scientist.

Migration With Dignity: A Legal and Policy Framework considers a variety of migration contexts and identifies policies that work and gaps that exist for considering the dignity of migrants. Meanwhile, The Methodology and Application of a Migration With Dignity Framework provides a methodology for considering the social and legal dimensions of the Migration With Dignity framework. The issue also discusses the intergenerationality of immigrants in adapting or assimilating into their new environment, and how mass media affects perceptions of migrants in host countries.

ELI is continuing its work on Migration With Dignity through a new grant from the United Institute of Peace, which explores the potential of the framework to prevent and mitigate conflicts. Through research, dialogue, technical assistance, and capacity-building, the Institute seeks to strengthen legal protections for people displaced across national borders through its Environmental Displacement and Migration program.

Report on mining in Amazon identifies major corruption risks

In July, ELI and its partners contributed to Corruption in Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in the Peruvian Amazon, a study prepared for USAID as part of the agency’s Prevenir Amazonías project. The Prevenir project aims to prevent and reduce the three greatest threats to the Peruvian Amazon: wildlife trafficking, illegal logging, and illegal mining. According to USAID, the project “works with the Government of Peru and civil society to improve the enabling conditions to prevent and combat environmental crimes.”

The guide represents the third in a series of reports developed by ELI for the project. The first, published in 2021, discussed the incorporation of wildlife trafficking into Peru’s organized crime law. Another, released in 2022, detailed best practices for prosecuting and sanctioning wildlife trafficking crimes.

The new report identifies corruption risks in the value chain of the gold derived from artisanal and small-scale mining in the Peruvian Amazon. In doing so, the report addresses the complex reality of mining in an analytical and evidence-based manner. Collaborating with local experts and professors, ELI analyzed interviews and conducted surveys of stakeholders involved in the gold mining value chain, including government officials, specialized prosecutors in environmental matters, and the chiefs of Amazonian Natural Reserves in which illegal mining often takes place.

The report then proposes regulations and governance mechanisms to mitigate these risks.

Sandra Nichols Thiam, ELI associate vice president of research and policy, served as project manager, and Elissa Torres-Soto, staff attorney, served as principal researcher and writer. Research Associate Georgia Ray, Staff Attorney Kristine Perry, and Visiting Attorney Vera Morveli also contributed to the research.

Geared toward policymakers, the study pinpoints the incidents where corruption is more likely to occur, and the factors that make corruption more likely. The Prevenir project is now focused on conducting outreach to spur dialogue and action on the report’s recommendations, especially to members of the Peruvian Congress who are beginning to address these issues.

ELI’s work on the Prevenir project situates within the Institute’s longstanding Inter-American Program. Since 1989, the program has worked in more than 20 countries in the region, with an extensive network of local partners to promote strategies of sustainable development and the conservation of natural resources.

In coming years, ELI plans to release another report under the Prevenir project on the use of amicus curiae in environmental crime cases in Peru, aimed at law students and members of NGOs.

ELI in Action Dialogue on the right to a healthy environment

In July, ELI partnered with Delaware Law’s Global Environmental Rights Institute, Barry University’s Center for Earth Jurisprudence, the American Bar Association Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources, the ABA Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice, and the ABA Center for Human Rights to produce a series of webinars about the right to a healthy environment.

Last year, the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva formally recognized the right to a “clean, healthy and sustainable environment” and recommended that the UN General Assembly do the same. In the first webinar of the series, a panel of international leaders from the United Nations and the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University discussed what it might mean for the UN General Assembly to adopt such a resolution. In the second installment, human rights practitioners reviewed the United States’ position on the issue, which continues to evolve. And finally, the third webinar, featuring experts in environmental rights and justice, examined the extent to which states in the United States have recognized or might recognize a right to a healthy environment.

•

ELI’s Food Waste Initiative is publishing a series of research briefs to present takeaways from the Initiative’s research, spanning a range of topics important to food waste prevention, recovery, and recycling. In May, the Initiative released Social Science Literature Review on Value of Measuring and Reporting Food Waste, authored by Research Associate Margaret Badding and Senior Attorney Linda Breggin. The brief provides an overview of relevant social science literature on the behavioral implications of measuring waste or emissions. Research indicates that simply measuring these components can motivate behavior change, due to increased awareness as well as reputational and financial concerns of measuring entities.

In June, the Initiative also published An Overview of Multilingual Outreach, Translation, and Language Justice Resources. Implementing environmental initiatives requires clear communication with affected communities—including those that speak languages other than English. Written by Research Associate Jordan Perry and Senior Attorney Linda Breggin, the brief highlights best practices for effective and inclusive multilingual outreach and document translation. To be most helpful to organizations with limited time and funds, these best practices are pulled from ready-to-use resources such as checklists and toolkits.

•

Under the Clean Water Act, states, territories, and tribes restore water quality in part by implementing Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs), which set a maximum level of a pollutant allowed in a given body of water. Evaluating the effectiveness of TMDLs is challenging, yet vital for revealing whether a TMDL and implementation actions are working or should be revised.

In June, ELI published Evaluating the Water Quality Effects of TMDL Implementation: How States Have Done It and the Lessons Learned, a report highlighting the diversity of approaches to evaluating the water quality effects of TMDL implementation. The document explains some of those methods and conveys lessons learned. It also details terminology challenges and identifies relevant resource materials. By facilitating communication among water quality programs, the document aims to generate new ideas and ensure that future TMDL restoration efforts are more effective and efficient.

•

This past year, ELI hosted a workshop series on Communicating Complex Science: The Challenge of Sea-Level Rise. Funded by the National Science Foundation’s Paleoclimate Program and co-hosted with George Washington University Law School, these discussions brought together scientists, lawyers, and policy professionals to examine opportunities in communicating the science of sea-level rise.

The initial session, focused on explaining the science and attributing the impacts of sea-level rise, was held in November. The panel featured presentations by scientists Andrea Dutton from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Ben Strauss from Climate Central. Robin Craig from the University of Southern California Gould School of Law facilitated a conversation to set the stage for subsequent sessions on the implications for law and policy.

In May, a follow-up session focused on the legal and policy landscape of sea-level rise included presentations from Astrid Caldas from the Union of Concerned Scientists, Jeffrey Peterson, author of A New Coast, Thomas Ruppert from Florida Sea Grant, and Robin Craig.

ELI Advances Peacebuilding, Ocean Conservation at UN.

ELI Report

Environmental Liability Using civil lawsuits to protect biodiversity and expand the policy toolkit for conservation

The harmful exploitation of resources — including illegal wildlife trade, fishing, and logging — is one of the top two factors devastating global biodiversity and driving species to extinction. It damages rural livelihoods, robs countries of badly needed revenues, and undermines conservation efforts.

Most countries rely on criminal and administrative enforcement to counter illegal wildlife trade. While these responses can impose fines and imprisonment, they are not focused on remedying the environmental harm.

An international group of conservationists, lawyers, and economists, including ELI Visiting Scholar Carol Adaire Jones and ELI Vice President for Programs and Publications John Pendergrass, is now advocating for the use of environmental liability suits to counter the illegal exploitation of resources and protect biodiversity. Unlike criminal and administrative procedures, these suits can hold responsible parties liable for remedying the harm they have caused, through actions including habitat restoration, species protection, public apologies, and education.

Funded by the U.K. Government’s Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund and led by Jacob Phelps of Lancaster University, the team advocates that conservation liability suits be used strategically against defendants involved in illegal wildlife trade with the financial means to provide remedies. These include corporations and organized crime groups who are held accountable for restorative actions, typically as a complement to criminal prosecution.

In addition to publishing a paper in Conservation Letters, the team released a guide, Pioneering Civil Lawsuits for Harm to Threatened Species: A Guide to Claims With Examples From Indonesia, which is intended to inform NGOs, government officials, prosecutors, academics, and judges.

Prior ELI research highlighted that laws providing a legal right to remedy for a wide range of environmental harms are already in place in many biodiversity hotspots, including Brazil, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia, Mexico, and more. However, these laws are seldom used for a number of reasons. In some cases, governance challenges such as corruption may be a factor. Other impediments include a lack of awareness of the law and a dearth of implementing guidance. In particular, one of the problems cited is difficulty in valuing the damages.

To address this issue, the guide builds on what is called the restoration-based approach for valuing claims. This method values damages based on the cost of restoration projects to remedy the harm to biodiversity and compensate for losses incurred until the resources recover, rather than placing a value on the harm done. Following the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill and the subsequent passage of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, the approach was pioneered in the regulations written to implement the OPA, for which ELI's Jones served as lead economist.

In the United States, the restoration-based approach to valuing damage claims — which has been widely adopted for other liability statutes — has been shown to expedite the restoration of resources after a case is resolved. This approach is also more readily transferable to developing countries than putting a dollar value on the harm.

The report guides practitioners and academics through key concepts and procedures for environmental liability lawsuits, including seeking, presenting, and executing legal remedies. The guide, journal article, and related policy resources can be found at conservation-litigation.org.

Cities can reduce food waste through climate action planning

Cities across the country have pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and develop climate action plans that outline the steps they will take to achieve these goals. However, most existing plans contain few, if any, food waste-related actions. A report by ELI in partnership with the Nashville Food Waste Initiative, A Toolkit for Incorporating Food Waste in Municipal Climate Action Plans, provides model provisions for addressing food waste in local planning, enabling cities to reduce both food waste and greenhouse gas emissions simultaneously.

Climate action plans offer an ideal opportunity for cities to address food waste, a major — yet often overlooked — contributor to climate change. In 2019, 35 percent of food in the United States went unsold or uneaten, leaving a greenhouse gas footprint equal to 4 percent of U.S. emissions. Research by Project Drawdown has identified reducing food waste as one of the top three most impactful solutions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions worldwide.

Addressing food waste also garners many benefits beyond climate change mitigation. Reducing wasted food alleviates food insecurity, conserves natural resources, and saves money by decreasing food purchasing and waste disposal costs.

The toolkit provides a menu of options that includes measures to prevent food waste, rescue surplus food, and recycle food scraps. It is intended to facilitate the widespread adoption of food waste provisions in local climate action and sustainability plans by truncating the time and effort that would be required if a municipality had to start from scratch.

In addition to providing model provisions, the toolkit includes links to example provisions in existing sustainability plans. Strategies and approaches highlighted in the toolkit include policies and ordinances, public awareness and education, incentives and funding, leadership and recognition initiatives, and environmental justice-related efforts.

Nature-based solutions minimize the impacts of disasters

Natural disasters pose a huge risk to people, ecosystems, and property — a risk that will only increase with climate change. One solution is to invest in nature-based hazard mitigation strategies, also referred to as natural or green infrastructure. These actions conserve or restore nature, such as wetlands and floodplains, or use green infrastructure projects like rain gardens, all to minimize the negative impacts of natural disasters.

Nature-based solutions can offer a more cost-effective alternative to “gray” infrastructure, which also increases habitat and biodiversity. Recently, a growing number of funding opportunities through the Federal Emergency Management Agency aim to encourage such strategies. However, to date relatively few nature-based projects have been funded with available grants.

Government entities can develop a strong foundation to apply for this funding by including nature-based strategies in their hazard mitigation plans. These plans are required of states, tribes, and locales for certain kinds of disaster mitigation funding, including grants from FEMA. Plans identify natural hazard risks to communities, create goals for hazard mitigation, and outline actions to address risks.

This spring, ELI released Nature-Based Mitigation Goals and Actions in State and Tribal Hazard Mitigation Plans, a study evaluating to what extent plans are incorporating nature-based goals and actions. Based on a review of all 50 states’ mitigation plans and a small subset of tribal plans, the report identifies a range of practices across jurisdictions, and analyzes areas for improvements in developing nature-based strategies. The study also includes specific plan language that could be used by governments in the future.

In tandem, ELI published an accompanying report, Nature-Based Mitigation Goals and Actions in Local Mitigation Plans, based on an analysis of over 100 local hazard mitigation plans. Both reports identify a number of paths to greater use of nature-based strategies. Although many plans include nature-based goals and actions, government entities can focus on planning for realistic prioritization of these projects. Funding, implementing, and monitoring these projects are also important next steps. Among other recommendations, more demonstration projects, including assessing outcomes with data and monitoring, can also exemplify the benefits of nature-based projects and encourage others to follow suit.

Using Liability Lawsuits to Protect Biodiversity.

Food Waste Co-Digestion at Water Resource Recovery Facilities: Business Case Analysis

Co-digestion of food wastes with wastewater solids at water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) can provide financial benefits to WRRFs as well as a broad range of environmental and community benefits. Co-digestion is a core element of the wastewater sector’s “Utility of the Future” initiative, which envisions a new business approach for pioneering WRRFs to create valuable energy and nutrient products via the recovery and reuse of residuals from the wastewater treatment process.

Real Benefits Fostering Food Scrap Recycling

Between 30 to 40 percent of food is wasted along the supply chain, from processing through in-home and dining-out preparation and consumption. Worse, only 5 percent of the waste is currently diverted to compost or anaerobic digestion facilities that can break down scraps and recycle them into the environment. The other 95 percent has considerable environmental, social justice, and cost implications. As a result, the federal government has set a goal of reducing food waste by 50 percent by 2030.

ELI’s Food Waste Initiative conducts research and collaborates with stakeholders to meet the federal goal by designing and implementing government policies and public-private initiatives to promote food waste reduction, edible-food donation, and diversion of remaining food waste from landfills and waste-to-energy plants toward productive uses.

In addition, I serve as the project coordinator for the Nashville Food Waste Initiative, a project of the Natural Resources Defense Council. In 2015, NRDC picked Nashville as its pilot city for developing high-impact local policies and actions to address food waste. NFWI works with the government of Nashville and Davidson County, as well as a wide range of business and nonprofit stakeholders, to create models for cities around the country.

NFWI’s efforts focus on preventing food waste and rescuing surplus food to feed those struggling with hunger — the two highest-priority strategies. But, NFWI also focuses on food scrap recycling which, although a lower priority, plays a key role in efforts to divert wasted food from landfills and prevent associated methane emissions and nutrient loss.

NRDC’s 2017 report “Estimating Quantities and Types of Food Waste at the City Level” found that as much as 178,920 tons of food are wasted annually in Nashville, and that industrial, commercial, and institutional generators are responsible for approximately 67 percent of this waste.

Motivated in part by these findings, ELI Research Associate Sam Koenig and I interviewed over 25 relevant Nashville stakeholders — including state, regional, and local government officials, waste management companies, advocates, and generators — in an effort to identify the barriers.

ELI recently published the findings in a Landscape Analysis of Industrial, Commercial, and Institutional Food Scrap Recycling in Nashville. The report outlines specific actions that key actors, such as local governments, businesses, and nonprofits, can take to build infrastructure and increase food scrap recycling in Nashville.

Our research found that Nashville’s existing infrastructure is limited (with only one nearby commercial organics composting facility and three organics haulers), meaning that increased capacity will be necessary if the area is to establish a robust and resilient food scrap recycling system.

NFWI points to several policies and practices that could foster sustainable food scrap recycling infrastructure. Interviewees suggested that government subsidies for organics recycling businesses or a government procurement policy that encourages the use of finished compost products in construction and landscaping projects could spur infrastructure growth. And, streamlining the state permitting process for new organics processing facilities could lower the barriers to entry for prospective processors. In addition, the creation of a solid waste authority that operates as an enterprise fund could make it easier for Nashville’s government to finance new infrastructure.

NFWI’s research concluded that in Nashville less than 1.5 percent of food scraps are recycled. Practices are limited by numerous barriers, including low awareness of the impact of food waste and benefits of food scrap recycling, the comparatively low cost of landfilling, the need for employee education and training, and the lack of space for food scrap bins in kitchens or on loading docks.

NFWI’s research, however, also identified several steps that can be taken to address these barriers, including education, financial incentives for industrial, commercial, and institutional generators, and limits on landfilling organic wastes.

The report comes at a pivotal juncture, as Nashville’s population is growing at triple the national average, and the landfill upon which it predominantly relies is quickly reaching capacity. Moreover, it recently joined the handful of cities that have set zero waste goals and is currently in the process of developing a long-term zero waste master plan.

The NFWI-ELI report will help motivate stakeholders to take action on food scrap recycling. Our study contains valuable information for other cities that would like to expand their food scrap recycling infrastructure and practices.

Real benefits foster food scrap recycling.