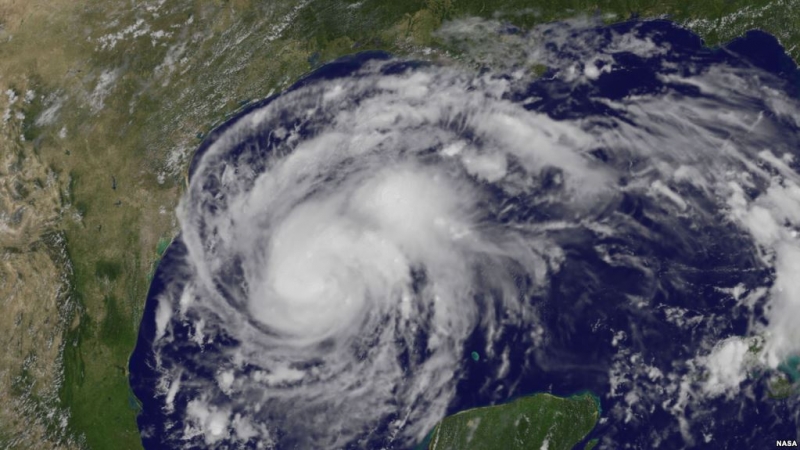

While EPA under Administrator Scott Pruitt seeks to drastically reduce the social cost of carbon (SCC), insurers already know that 2017 delivered the most expensive Atlantic hurricane season ever for insurance companies. Beyond this year, since the 1980s, the annual average losses to insurers have risen, increasing over the last decade from $10 billion to about $50 billion. “Insurers are rightfully worried that, in the long term, climate change could devastate their industry,” reported the Los Angeles Times. While Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico flood, EPA recalculates, and insurance companies add up their costs.

|

Meanwhile, in case you haven’t heard, on October 10 EPA released its plan to repeal the Clean Power Plan along with a 198-page analysis that revamps the Agency’s previous SCC calculation. In sharp contrast with the Obama EPA’s 2020 inflation-adjusted calculation valuing a ton of carbon reduction at $45, the Trump EPA calculates the cost at between $1 and $6.

Complex SCC Models

Not that the SCC calculation is a straightforward number crunch. As Elizabeth Stanton wrote in the Nov/Dec 2011 issue of The Environmental Forum, when the price was “a measly $21 per ton,” various “nested assumptions” can each change the bottom line. And a July 2011 ELI Policy Brief by Ruth Greenspan Bell and Dianne Callan provides a plain English overview of the subject that made key points about the SCC’s use and limitations. By 2011, SCC discussions were well under way as a vital policy matter because, as Yale University economist William Nordhaus wrote in a 2016 paper, it is “the most important single economic concept in the economics of climate change.” Regulatory decisions can live or die by the number.

Because the SCC requires numerous judgment calls, the vastly different Obama and Trump EPA calculations reveal, if nothing else, the contrast between a president who considered climate change to be the greatest long-term threat facing the world and a president who tweeted, “The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.” Pruitt, of course, reflecting his boss’s view, doesn’t see the link between carbon emissions and climate change.

The New (Ab)Normal

|

To me, a boat owner who was trying to help people during the Hurricane Harvey flooding in August put it most succinctly when he told The Dallas Morning News, “I’ve never seen anything like this before. This ain’t normal.” Or, perhaps more accurately, as National Center for Atmospheric Research scientist Kevin Trenberth and two colleagues wrote in an August 2015 paper in Nature Climate Change, “The climate is changing: we have a new normal.” Insurance companies that know something about risk seem to agree, and they’re putting that new (ab)normality into their premiums. But at EPA, the analysts are taking out judgments that point to a problem deeply impacted by carbon. Presto! No need to regulate emissions.

Going beyond the immediate perception that things aren’t normal, earlier this year the Scientific American reported that on April 21 the pristine Hawaiian Mauna Loa Observatory for the first time ever measured CO2 readings in excess of 410 parts per million (ppm). Noted the article, “Carbon dioxide hasn’t reached that height in millions of years. It’s a new atmosphere that humanity will have to contend with, one that’s trapping more heat and causing the climate to change at a quickening rate.” In January, Ralph Keeling, director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography’s CO2 Program in San Diego, told Yale Environment 360 that the Mauna Loa data showed, “We’re in a new era. And it’s going fast. We’re going to touch up against 410 pretty soon.” When Keeling’s father in 1958 first started measuring CO2 in the atmosphere, CO2 levels were at 316 ppm, a bump up from the 280 ppm levels prior to the industrial revolution.

The scientific community and ordinary citizens recognize we’re in a new (ab)normal, but under its current administrator, EPA—created in 1970 to protect the environment—isn’t making the CO2 connection that has been made so clearly by scientific theory and data. So what else is new?