For the past seven months, an effort has been underway to change the way we regulate biotechnology—an effort that involves the White House (driven by the Office of Science & Technology Policy and including CEQ, OMB, and the U.S. Trade Representative); three of the most important regulatory bodies in our government: EPA, FDA, and USDA; and the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). No regulatory modernization initiative in recent history has come close to this effort in terms of the level of government engagement and potential scope of impact. The target is the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology, first put in place by the Reagan Administration in 1986 and updated once in 1992 (to set your chronological clock, that is the year when Bill Clinton entered the White House, Unforgiven won big at the Oscars, and Achy Breaky Heart overtook the radio).

In 1992, companies spent around $5 billion globally on biotech research and development (R&D). R&D spending now tops $40 billion, and the global biotechnology market is estimated to exceed $400 billion in 2017. Here at home, the next wave of biotechnology innovation—driven by advances in areas like synthetic biology—is rolling across the industrial landscape. Over the past two years, 75 new companies were created in the synthetic biology field in the United States, bringing the total to over 300. In 2015, synthetic biology startups attracted over $500 million in venture capital investments, an amount that is expected to rise.

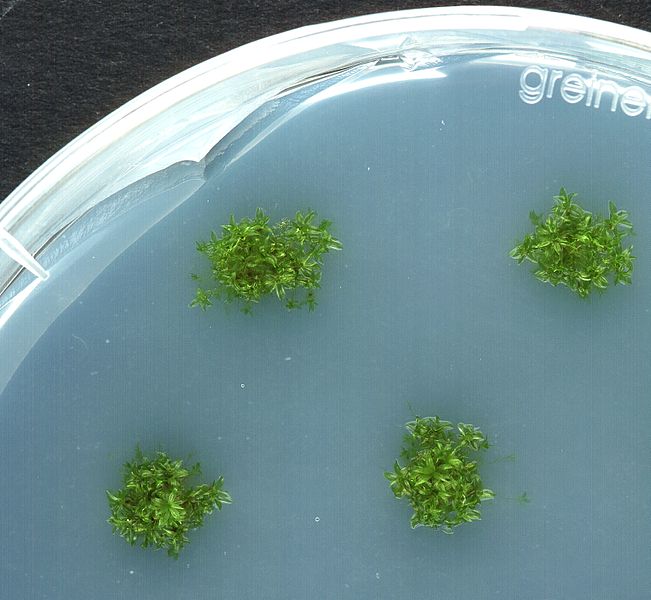

|

|

Photo by Sabisteb |

Work in this field could have transformational impacts on the environment. Advances in synthetic biology could provide us with plants that fix their own nitrogen, the ability to drive out vector-borne diseases that threaten humans and other species, and new ways to produce protein for a hungry planet. At a more fundamental level, biology would facilitate the shift away from hydrocarbons and chemical synthesis to a carbohydrate economy based on biology as a design and manufacturing paradigm. But engineering biology will also create risks and we will need a highly transparent and efficient regulatory framework that fosters responsible innovation, especially for startups.

That is why there is much at stake. If you missed this regulatory reform effort, it is understandable. The White House announced their intent at 3 pm the Friday before the Fourth of July weekend, just as a large percent of our policy apparatus, and the press that covers it, was on their way to the beach. The plan had three important components: (1) the development of a long-term strategy (released on September 22nd); (2) an update of the coordinated framework that clarifies the roles and responsibilities of EPA, FDA, and USDA (released on January 4th); and (3) an independent analysis of the future landscape of biotechnology products by NASEM (expected to be released within the next 2-3 months).

The recent release of the update stressed that, “While today’s release of the 2017 Update to the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology represents remarkable progress by the EPA, FDA, and USDA to modernize the regulatory system for biotechnology products, much work remains. The findings by the NAS report on future biotechnology products, along with the comments submitted in response to the proposed update of the coordinated framework, and information gathered during the three public engagement sessions that EPA, FDA, and USDA, hosted in 2016, will be considered by these agencies in order to inform ongoing and future agency activities.”

If we care about the future of biotechnology, the jobs it can create, and its potential to provide breakthroughs in sectors ranging from medicine to energy, it will be important to keep this effort going.

David Rejeski directs the Technology, Innovation, and the Environment Project at ELI. He is a member of the NASEM Committee on Future Biology Products and Opportunities to Enhance Capabilities of the Biotechnology Regulatory System.