With the 50th Anniversary of Earth Day still on our minds, air quality is thriving throughout the United States’ most populous areas. It is a goal long fought for by leaders in environmental law and policy, but it has only been achieved with the cost of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic.

The novel Coronavirus has ravaged communities across the country, bringing economies to a screeching halt and costing hundreds of thousands of lives. Efforts to flatten the curve have focused heavily on individual states issuing stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders. These orders vary state by state: some are issued by executive order, others are merely guidance; some were issued at the onset of the pandemic hitting the United States, while others are more recent and long-debated issuances; some indicate strict, statewide requirements, and still others have declined to issue any statewide proclamations, instead allowing major cities to issue their own, or opting for none altogether.

The Environmental Law Institute has explored how this pandemic began and how it can be prevented in the future, workplace risk management and responses to COVID-19, and how the pandemic gives China and California a glimpse of a low-emission future. We now turn to our national community: what does cleaner air in the United States mean in the context of this global pandemic?

Much has been said about continuing efforts toward cleaner air and reduced pollution in support of an environmental rhetoric. Grassroots efforts, the Green New Deal, decades of implementing the Clean Air Act, and much more have all pushed the United States toward the goal of improved air quality. A goal that is now largely being achieved—but at an unimaginable cost.

At a time when greater respiratory resilience is needed more than ever, the pandemic draws attention to the serious health effects of air pollutants, especially for vulnerable populations. EPA’s Air Quality Index (AQI) reflects ambient air monitoring of carbon monoxide, ground-level ozone, nitrogen dioxide, particle pollution (including PM2.5 and PM10), and sulfur dioxide. As the agency notes, “The higher the AQI value, the greater the level of air pollution and the greater the health concern.”

|

|

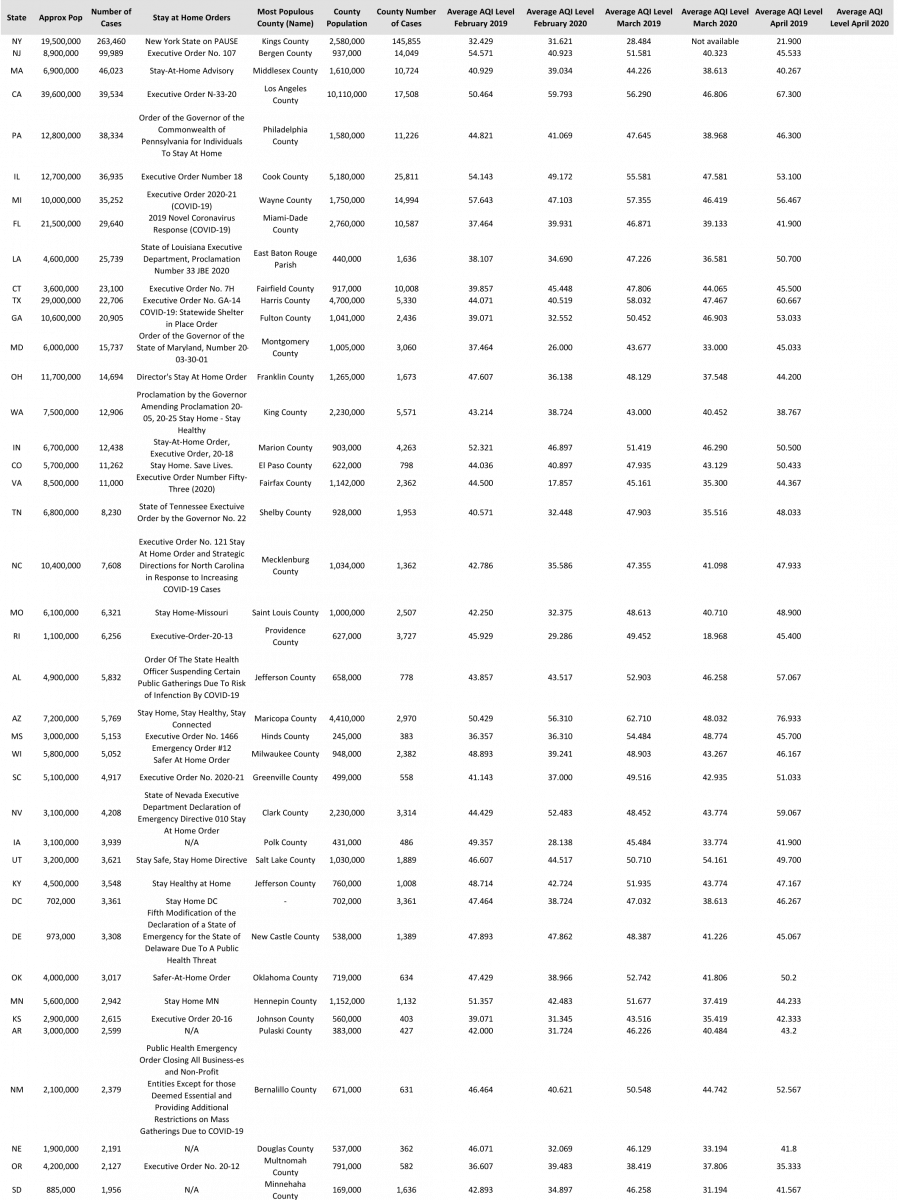

Compiled and calculated using EPA: Air Quality Index Daily Values Report, NYT: Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest Map and Case Count, & NYT: See Which States and Cities Have Told Residents to Stay at Home (updated 6/15/20) |

The findings (click on the image to the right to download the results) provide a snapshot of where we are as a country: the top states by number of reported COVID-19 cases; the stay-at-home and related orders and guidance provided; the most populated counties in each of these states and the number of reported COVID-19 cases; the calculated average AQI levels for February, March, and April 2019; and the calculated average AQI levels for February and March 2020 (April forthcoming). The results are striking.

Coronavirus has already shown the capacity for radical (good and bad) and rapid change. In a post-COVID-19 United States, there is significant opportunity for maintaining lower AQI levels through stricter regulations, advances in new technology, increases in renewable energy, and much more. Imperatively, there also exists an opportunity to shift our cultural view to one that accepts and insists on the equitable implementation of laws, measures, practices, and policies that adhere to and acknowledge that poor air quality poses a grave danger to public health.

This is not news to economically disadvantaged communities nor to communities struggling with environmental injustice. But as these communities are increasingly hit by the global pandemic, and as communities across the United States are affected to varying degrees as well, there finally presents a coalescing desire to reduce air pollution—for good, for environmental justice, and for public health.

The nexus between air quality, socioeconomic drivers of inequality, and COVID-19 will be explored in our next blog.