In the shadows of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River has long been known as D.C.’s forgotten river due to the effects of heavy pollution and neglect. With recent efforts to remediate the river, the Anacostia and its surrounding neighborhoods are a site of urban development and environmental gentrification.

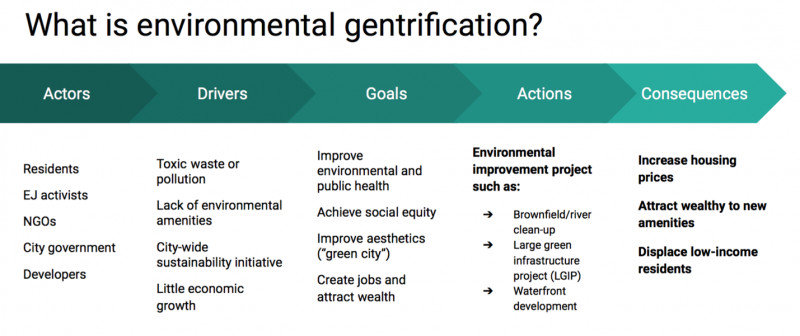

The concept of gentrification might be well known, but what is environmental gentrification? Simply, it is the process by which environmental improvements make a neighborhood more attractive, thus increasing housing prices and displacing the low-income residents of the community. However, this process is actually much more complex, involving a variety of actors each with unique motivations and goals (Figure 1). In some instances, local governments and developers, unaware of a “green” project’s connection to issues of social justice, treat environmental quality as another consumer amenity that can spur economic growth. The “green” projects that result, such as large parks or green transportation corridors, attract affluent groups and displace marginalized residents. Other times, these environmental projects are explicitly designed to benefit vulnerable, marginalized residents, yet still ultimately displace them. This paradox naturally raises the question: can sustainability initiatives be compatible with environmental and social justice? Alternatively, should low-income residents have to reject environmental amenities to resist gentrification?

Figure 1. General model of the environmental gentrification process. While the actors, drivers, and goals vary and interact in different ways across examples of environmental gentrification, the actions and consequences (bolded) are the same. Model created by author.

When the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, the Anacostia River was heavily polluted with tires, plastic car parts, toxins, PCBs, and pesticides. 96% of the tidal wetlands of the Anacostia Watershed had also been destroyed. In 1998, the Navy Yard district near the river was classified as a Superfund site. Furthermore, the poor functioning of DC’s sewer systems resulted in raw sewage and stormwater pollution in the Anacostia for decades. Besides its environmental concerns, the river also symbolically divides the majority-white and affluent population on the west side of the river with the minority and low-income residents of Wards 7 and 8 on the east side. Accordingly, the public health impact of Anacostia’s contamination has disproportionately affected the primarily minority communities living along the river—a clear case of environmental injustice.

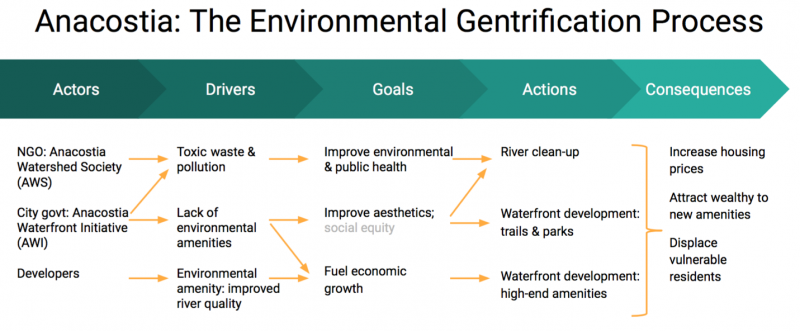

Since 1989, the local NGO, Anacostia Watershed Society (AWS), with its vision of a swimmable and fishable river by 2025, has been working to clean up the Anacostia and encourage public stewardship of the river. As of 2000, the D.C. government’s Anacostia Waterfront Initiative (AWI) has promoted the economic revitalization of the waterfront and linkage of neighborhoods along the river through numerous projects, including various nature trails to increase accessibility to the Anacostia. As the river quality has improved, developers are seizing waterfront property as a valuable commodity to construct upscale neighborhoods on the west side. While development projects have thus far largely been confined to the west side of the river, residents on the east side cross over to the west side to enjoy the new public spaces, including Yards Park and the Nationals Stadium. However, these investments on the west side have drawn public attention to the Anacostia and indirectly increased land values on the east side of the river as well, initiating gentrification. Due to the prioritization of economic over equitable development, waterfront development on the Anacostia has generally failed to address the concerns of marginalized residents on the east side of the river (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Model of the environmental gentrification process in Anacostia, D.C. For the AWI, economic growth and better city aesthetics were primary goals while social equity was a secondary concern (Anvi and Fischler 2019). Model created by author.

Despite the AWI’s largely growth-oriented strategy, one of its projects—the 11th Street Bridge Park—seems to be breaking this mold. To repurpose the defunct bridge spanning the Anacostia River, the city’s director of planning, with an explicit vision of equitable development, sought to transform the obsolete infrastructure into a bridge park “that would traverse a historically divisive social and economic barrier.” The local NGO in charge of the project’s implementation shares similar goals with the Bridge Park; both seek to revitalize communities on the east side of the river through equitable inclusion. To accomplish this vision, the NGO is collaborating with community members, city agencies, and nonprofits to preserve and build new affordable housing, including through a community land trust. The Bridge Park’s Equitable Development Plan highlights its other approaches to address gentrification, such as a workforce agreement to maximize the number of residents in Wards 6, 7, and 8 placed on construction and post-construction jobs of the Bridge Park and a community benefits agreement with developers to ensure that local businesses occupy redeveloped spaces. These proactive measures aimed to involve the community in the planning process and resist gentrification are expected to create an inclusive and open green space that benefits the economic, social, and public health of existing populations.

The Anacostia is just one neighborhood wrestling with the challenges of environmental gentrification. From New York City to Chicago to Atlanta, this phenomenon demonstrates that sustainable development is a balancing act. Specifically, these cases highlight that resisting gentrification requires planners that are not only motivated to design projects that explicitly address the needs of all residents, particularly marginalized residents, but also have the institutional capacity to do so. Hence, multisectoral alliances among environmental, housing, and social justice groups, and an equity-minded local government are critical to unite an environmental project under the shared goal of achieving environmental justice and create the institutional capacity to achieve it.

The Anacostia is just one neighborhood wrestling with the challenges of environmental gentrification. From New York City to Chicago to Atlanta, this phenomenon demonstrates that sustainable development is a balancing act. Specifically, these cases highlight that resisting gentrification requires planners that are not only motivated to design projects that explicitly address the needs of all residents, particularly marginalized residents, but also have the institutional capacity to do so. Hence, multisectoral alliances among environmental, housing, and social justice groups, and an equity-minded local government are critical to unite an environmental project under the shared goal of achieving environmental justice and create the institutional capacity to achieve it.

Since the environmental gentrification process generally involves multiple actors with potentially diverging interests, addressing it first requires an awareness that an environmental improvement, even for the sake of environmental justice, has the potential to result in inequity. Moving forward, community engagement in and ownership of the project will make it possible for vulnerable residents to embrace the environmental change they wish to see and remain in their communities to enjoy its benefits in the long run.