Early in the fall of 2016, there was growing cause to celebrate the international momentum building around climate mitigation. In October, United Nations actors reached agreements to limit airline emissions and later HFCs. On November 4, the Paris Agreement under the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change went into effect. Then, four days later, Donald J. Trump was elected president, casting doubt on the U.S. climate commitments made by President Obama’s Administration. Though his Tweets and stump speeches may not equate directly to his eventual climate policy, the surprise election results have certainly caused consternation among advocates of climate mitigation and adaptation. As Jay Pendergrass wrote, extracting the United States from the Paris Agreement may not be as simple as the President imagines, but certainly an executive branch headed by climate deniers could turn around federal initiatives aimed at reducing GHG emissions (the Clean Power Plan), promoting resilience (President Obama’s Task Force on Climate Preparedness and Resilience), and investing in climate research and renewable energy technologies (the invigorated DOE Loan Programs Office). But, potential for a Trump train derailment of climate action seems less devastating when one considers the impact non-state actors, in the United States and abroad, can have on achieving the goals laid out by the Paris Agreement.

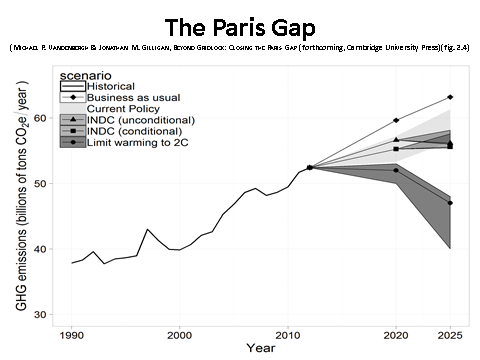

Even before the election, global climate mitigation faced an uphill battle. The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) submitted under the Paris Agreement in 2015 are not nearly enough to meet the agreement’s stated goal of limiting the average global temperature increase to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius. As Vanderbilt law professor Mike Vandenbergh has pointed out, although the INDCs will be revisited every five years and can only become more stringent over time, closing the “Paris Gap” may be up to private actors—institutions, companies, civil society organizations, and individuals.

|

Graphic from forthcoming book Beyond Politics: The Private Governance Response to Climate Change by Mike Vandenbergh and Jonathan Gilligan |

ELI’s Keare Policy Forum, held on October 25, brought together a panel of multidisciplinary experts to discuss some of the extrajurisdictional mechanisms that will play a role in determining the global climate future. The conversation showed that private actors have important roles to play and may even help keep the Paris Agreement on track, despite potential threats from the White House. The panel highlighted two ways private actors can help close the gap, and hinted at a third that may be more important now than ever.

First, private actors, from individuals to multinational corporations, can help steer market forces in climate-positive directions. Consumers can make climate-sensitive choices about the products and services they purchase. This is just as true for large corporations as for individuals. Astri Kimball, a Senior Policy Advisor at Google, explained the business case for the tech giant’s commitment to purchasing all of its data center energy from renewable sources. Google considers using renewable energy a hedge against price volatility and Astri described how state policies influence the company’s citing decisions. The Natural Resources Defense Council’s Sameer Kwatra discussed how the financial sector is responding to the climate crises, including the issuing of green bonds and the development of green banks.

Second, corporations and NGOs can help governments meet their goals both by holding them accountable to their commitments, and by building public support for implementation. Bob Perciasepe, the President of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES), noted that the tone struck by multinational corporations before and during Paris gave the negotiators a confidence boost that helped pave the way for the final agreement. Continued, vocal support for strong climate action can show policymakers and the public that businesses accept the reality of climate change, and that being proactive makes good business sense. Ken Berlin outlined some roles civil society can play. As the President of the Climate Reality Project (CRP), Ken highlighted ways CRP is engaging governments around the world to identify policy gaps and hold national governments accountable for the commitments they made. Ken also pointed to the role of NGOs in building the public support needed to pressure governments to implement the policies that help achieve their goals.

Through a post-election lens, one other role of private actors seems critically important. As Mike Vandenbergh pointed out, major contributions by non-state actors could help beat the “solution aversion problem” exhibited by many in the United States, and bring political consensus to fighting climate change. If corporations, religious and cultural institutions, and other non-state actors engage the public and governments on climate issues, it adds legitimacy to the conversation that some would say has been lost because of the discourse among politicians. If companies step up and say, “Here is what we are doing despite the fact that regulations do not require it,” if universities say, “We are divesting from fossil fuels because it is better for our students,” and if religious leaders say, “Climate change is a moral imperative,” it can help the discussion stick to the facts, and keep it out of reach of politicians who crave the short-term benefits of climate denial publicity.

Now more than ever, thoughtful conversations need to happen at every level of society, formal and informal, public and private, about how to hold governments around the globe accountable for the commitments they made in Paris last December. It is crucial that private actors do everything in their power to move climate action forward, with or without our elected leaders.

The January/February 2017 issue of The Environmental Forum presents a transcript of the 2016 ELI Keare Policy Forum, which has been edited for space reasons and to improve clarity.