Greta Thunberg’s arrival in New York last month was highly publicized. So was her choice to travel via a “zero-emissions” yacht and her speech before the U.N. General Assembly. What many missed was that she also filed a complaint against five countries over their climate negligence during her visit. But before Greta, there was (is) Juliana (well, Kelsea). Kelsea Cascadia Rose Juliana is the leading plaintiff in Juliana v. United States, otherwise known as the Youth Climate Case. Supported by the nonprofit organization Our Children’s Trust, Juliana and 20 other youth plaintiffs sued the U.S. government in 2015 over its lack of action to combat climate change. Greta and Juliana’s cases are among a small but growing docket of climate-related litigation around the globe, cases that may become the Marbury v. Madison of climate case law.

So, why are they taking climate change to court? Judges hearing Julianaasked the same question. The claimants in Juliana argue that the government’s inaction to limit carbon dioxide emissions to 350 ppm by 2100 amounts to an infringement of youths’ right to life and liberty, a claim that rests on a triangulation of the Public Trust Doctrine, the Ninth Amendment, and the Fifth Amendment. But what concerns the 9th Circuit judges in Juliana is whether the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness includes the right to a clean environment. Further, to echo one judge’s question, what “affirmative action” could the court prescribe to combat in action in the absence of a single offending agency or law? While previouscases have pushed the Supreme Court into the realm of climate science, the premise has frequently been on technical grounds, rather than over fundamental constitutional principles. While government responses during both the Obama and Trump Administrations have centered around technical dismissals and the extent of judicial lawmaking, the plaintiffs’ fundamental question remains: does the Constitution protect your right to survive in a stable and healthy environment?

Juliana fits into a broader array of cases, which have been filed largely from the past decade, that form the bedrock of climate litigation. First argued in 2015, Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands was a claim presented by the Dutch environmental organization, the Urgenda Foundation, compelling the Dutch government to reduce emissions by 25% by 2020. Their claim invoked an article of the Dutch Civil Code that allows a public interest standing exception to sufficient and demonstrative personal harm, which a 2001 Hague District Court deemed to allow for the standing of “future generations.” Though the final decision is still pending, its preliminary ruling was one of the first high-profile ones in the world.

In Pakistan, farmer Ashgar Leghari sued the government in 2015 over its failure to implement its own climate policies from 2012. In his ruling, Pakistan’s chief judge wrote “environmental [and] climate change justice” are embedded in Pakistan’s Constitution, and that government “delay and lethargy of the State in implementing the Framework offends the fundamental rights of the citizens.” The ruling is notable in its specificity, calling out 21 individuals (by name!). Importantly, two-thirds of the court’s prescriptions had been fulfilled by the government by January 2018. Following the success of this suit, another suit was filed in Pakistan earlier this year by a “coalition of women” claiming that climate change disproportionately affects them, citing government inaction as a violation of equal protection. Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan impressed upon the world the potential abilities of the judiciary to enforce past promises.

The third and final precedent comes from Colombia, where 25 Colombian youth (ranging from ages 7 to 26) sued various bodies of the Colombian government, municipalities, and corporations to compel them to use their administrative cooperative capabilities to enforce their rights to healthy environment, life, health, food, and water. The suit is a special constitutional claim called a tutela, which invokes Article 86 of the Colombian Constitution, dubbed the “guardianship action” clause, in which rights are “violated or threatened by the action or the omission of any public authority.” Colombia’s Supreme Court sided with the claimants, writing that “the minimum subsistence, freedom, and human dignity are substantially linked and determined by the environment and ecosystem,” building on a previous decision that recognized natural entities as “subject to rights.” The Court ordered the government to “formulate and implement action plans to address deforestation in the Amazon,” a result akin to Leghari albeit far less specific, and without the same demonstrable results. The key to the case’s visibility, like Juliana, is its reliance on youth claimants. Two other ongoing cases, one in Canada and one in India, also rely on youth to bolster a case squarely in their country’s respective Public Trust Doctrines. The lead plaintiff in the Indian case, a 9-year old, pointedly maintains that all she is asking is for India to keep the promises it made a few years earlier at the Paris Climate talks.

There are some other cases, particularly in the international law realm, worth keeping an eye on. The Armando Ferrão Carvalho and Others v. The European Parliament and the Council case is a joint action by 10 families from countries around the world (from Portugal to Romania to Fiji), aiming to nullify three EU Directives that govern emissions from power, transportation, and buildings that have been made obsolete by recent EU climate policies. The second case involves a Peruvian farmer suing German energy company RWE so that they will reimburse his town 0.47% of what it spent on rebuilding from a devastating flood, the exact percentage of what the company contributes to global greenhouse emissions. Currently working its way through German courts, Lliyua could set a precedent for holding private companies liable for their emissions, a concept made feasible by increasingly sophisticated technology. Lastly, some cases rely on framing climate justice as a human rights issue, a vernacular more familiar to many international courts and legal bodies. Greenpeace Southeast Asia sued a list of 50 corporations known as the “carbon majors” over their contribution to ocean acidification, a case now before the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines. A new case has just been filed in the UNHRC by eight indigenous individuals from the Torres Strait Islands off Australia’s north coast, claiming Australia violated multiple articles of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights by doing nothing to combat sea-level rise. In countries like Australia, with a nascent legal theory of native title, couching climate action in the context of indigenous rights presents a transformative approach to achieving intersectional justice through the courts.

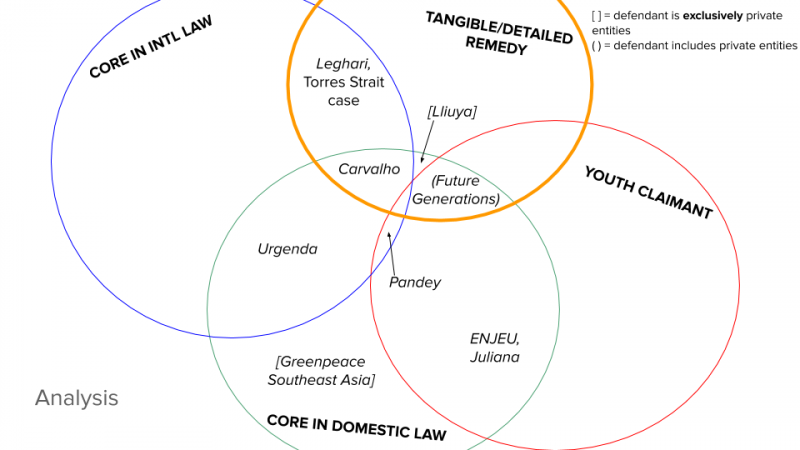

Figure 1. A visual analysis of the cases and their similar/contrasting motifs. Figure created by author.

While there is limited direct effect of these peer cases on the outcome in Juliana, the presence of common trends and themes expand the realm of possibility for climate litigation. For example, can climate change effects, particularly in the ways it encroaches on private property, be considered a violation of the Fourth Amendment? Looking at Leghari and Maria Khan, can an Equal Protection argument be made? Can the government be held accountable for climate change’s destruction of tribal land, a violation of its trust responsibilities to indigenous nations across the country? Courts may choose to ignore Juliana, but the growing trend of cases around the world tell us that this will not be the last challenge to fall on the Supreme Court’s lap. As climate petitions pile up, courts can choose between debating these difficult questions and finding themselves complicit in their silence.