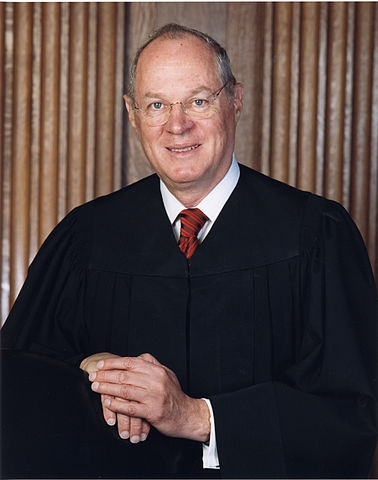

On June 27, 2018, Justice Anthony Kennedy announced that he will retire from the U.S. Supreme Court on July 31, 2018. Kennedy, who was nominated by former President Ronald Reagan and confirmed in 1988, became a crucial swing vote on a variety of environmental issues during his tenure. On July 11, 2018, ELI hosted John Cruden, John Elwood, and Richard Lazarus at a Breaking News webinar to explore the influence Kennedy has had on environmental law and to discuss the implications of his retirement from the Court for the future of environmental law.

A Farewell to Justice Kennedy

Justice Kennedy’s retirement at the end of this month has the potential to significantly affect environmental law for years to come. During his tenure on the bench, Kennedy has been a crucial deciding vote on a host of environmental issues, from the Clean Water Act (CWA) and Clean Air Act (CAA) to regulatory takings. As Richard Lazarus pointed out, Kennedy “wasn’t just the swing vote, he was the vote,” joining the majority opinion in all but one environmental case since he joined the Supreme Court in 1988. His departure from the Court is nothing short of significant.

All three webinar panelists were quick to name Rapanos v. United States and Massachusetts v. EPA as cases in which Kennedy has had the most lasting impact. In Rapanos v. United States, Kennedy authored his own concurring opinion, which provided an extensive explanation for how far EPA’s and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ jurisdiction extends to protect wetlands under the CWA via the “significant nexus” test. Kennedy’s concurring opinion in that case became the very basis for the Barack Obama Administration’s “waters of the United States” rule for regulating wetlands. In Massachusetts v. EPA, Kennedy was the crucial fifth vote in the Supreme Court’s ruling that: (1) Massachusetts had standing to sue EPA over non-enforcement of the CAA; and (2) that greenhouse gases are pollutants under the CAA and EPA has a statutory duty to determine whether and how to regulate them. Because Kennedy’s departure will almost certainly lead to the appointment of a more conservative Justice, cases like Rapanos v. United States and Massachusetts v. EPA have the potential to be overturned or at least have their reaches be significantly curtailed.

Kennedy’s Replacement

President Donald Trump has nominated Brett Kavanaugh, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, to fill the vacancy left by Kennedy’s retirement. Kavanaugh’s judicial philosophy is more conservative than that of Kennedy. He has a history of applying principles of textualism and originalism, which differ from Kennedy’s more pragmatic approach to judging. If confirmed, Kavanaugh will almost certainly rule more conservatively on environmental cases than his predecessor.

As a judge on the D.C. Circuit for the past 12 years, Kavanaugh has handled more energy and environmental cases than any of the other potential candidates for Kennedy’s seat. In many of these cases, as some have noted, Kavanaugh has construed EPA authority narrowly and often ruled in favor of regulated parties. In EME Homer v. EPA, for example, Kavanaugh wrote for a panel that rejected EPA’s Clean Air Interstate Rule, which regulates power plant emissions that cross state lines. In that case, Kavanaugh concluded that EPA had “transgressed statutory boundaries” when it required upwind states to reduce emissions by more than their own significant contributions to downwind states’ nonattainment. In Coalition for Responsible Regulation v. EPA, Kavanaugh dissented from a denial to rehear a decision upholding EPA greenhouse gas regulations introduced under the Obama Administration. There, he argued that EPA “exceeded its statutory authority” under the CAA to require stationary pollution sources to obtain permits for greenhouse gases. Kavanaugh’s opinions in these cases demonstrate his staunch application of textualism and his deep sense of separation of powers that make him inherently skeptical of EPA’s broad assertions of regulatory authority.

The Future of Environmental Law

Justice Kennedy’s retirement and the almost certain appointment of a more conservative Justice like Judge Kavanaugh will undoubtedly shift the Supreme Court in a direction less favorable to environmental protections. If confirmed, Kavanaugh will take a more originalist approach when deciding environmental cases, which means he will limit his focus to the statutory text at issue unless the U.S. Congress has directly spoken on the matter. Given that Congress has not been in the environmental law making business for some time, Kavanaugh will likely look to the text of the statute, and the text alone, to guide his rulings. Doing so takes away much of the flexibility that is advantageous to environmental litigation, making a regulatory agency like EPA more likely to lose when it tries to assert broad regulatory authority.

But the appointment of a more conservative Justice does not mean that the future of environmental law and policy is inevitably doomed. It simply requires the use of different tactics. For example, as others have noted, environmental lawyers should base their arguments on original intent and statutory text, as that is the language that conservative judges like Kavanaugh understand and apply when deciding cases. Even Kavanaugh has ruled in EPA’s favor on occasion when the statutory text was clear. For example, he wrote an opinion in American Trucking Ass’ns v. EPA upholding EPA’s review of California’s limits on emissions from transportation refrigeration units in trucks, and he wrote a panel decision in National Mining Ass’n v. McCarthy upholding an EPA program intended to address the environmental effects of surface coal mining on waterways.

So, while Judge Kavanaugh poses clear challenges, it’s not time to throw in the towel. Rather, it’s time to use new strategies and fight with ever more vigor.