An increasingly fast-paced technological world requires a restructuring in environmental protection strategy. In A New Environmentalism: The Need for a Total Strategy for Environmental Protection, ELI President Scott Fulton and Dave Rejeski, Director of ELI’s Technology, Innovation, and Environment Program, discuss how environmental protection could be organized and implemented in the future.

As the authors explain, “The total strategy of the future needs to create a much more robust option space for organizations and hedge against uncertainties. . . . What constituted a strategy 15, or even 10 years ago—analyze, plan, execute—no longer works in operating environments that are increasingly unpredictable, fragmented, and characterized by high rates of technological change, big data, crowd communication, young industries, and an incessant drive for competitive advantage.”

Their Comment, which runs in the September issue of ELR News & Analysis, offers a brief history of environmental protection, beginning with legal avenues of enforcement in the 1960s and 1970s, and the shift to business-established environmental norms and policies in the 1990s. Through the 2000s and into today, a “knowledge-based economy,” or economy of big data production, has emerged. Fulton and Rejeski argue that for the environmental movement to move forward, environmental norms must enter the networks of data and software.

The growing data-intensive network presents opportunities but also challenges. For example, because of big data, the United States has been able to increase monitoring of water quality, mapping of species, and growing connections between citizens and organizations who are concerned about the environment. On the other hand, understanding how glitches in software can impact environmental decisionmaking, or reckoning with how artificial intelligence may play a role in environmental policy and monitoring, could pose real challenges.

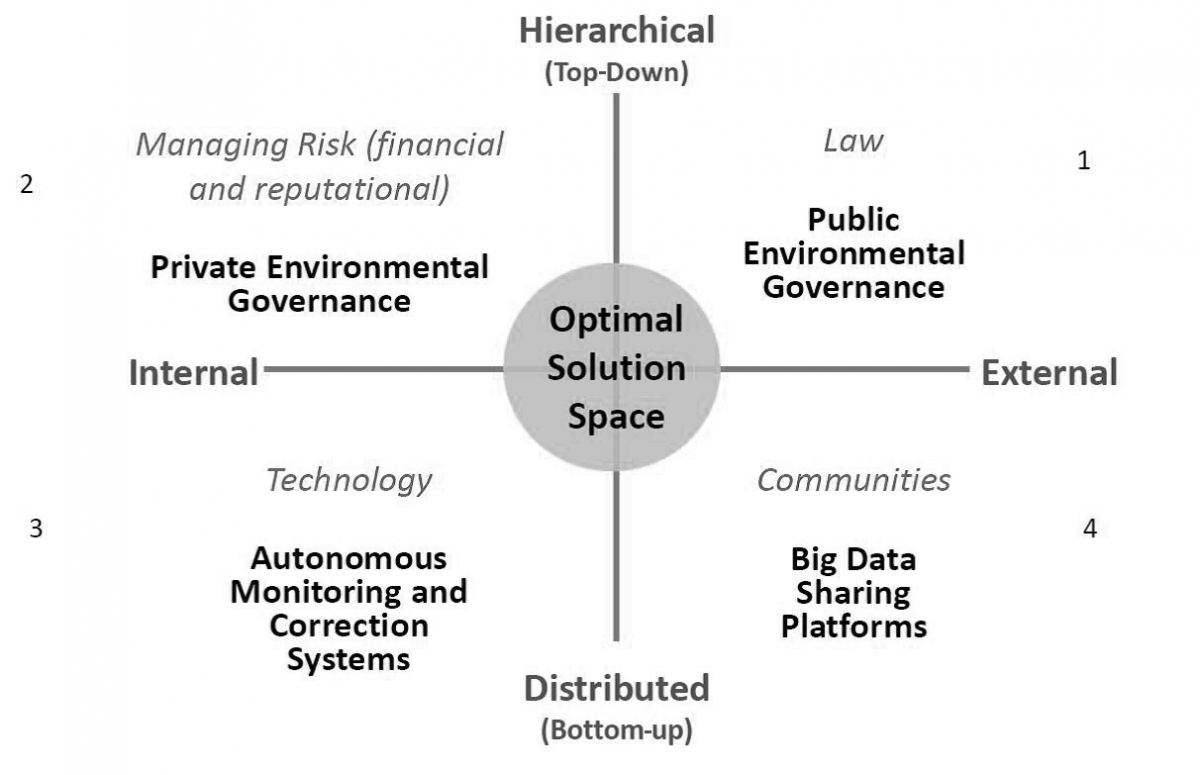

To help ensure transparency and accountability when managing and monitoring environmental quality in today’s big data setting, the authors developed “a new ecosystem of drivers” graphic to help illustrate this new paradigm (see Figure). The graphic’s four quadrants show the actors and structural organization of drivers. The Comment dives into detail about how the framework provides a starting point for questions, such as how to ensure that legal systems can anticipate manipulation of data, or how citizen-generated data can be used to improve environmental quality. For example, it could be used to examine how citizen-collected data offers amends to the Clean Water Act. The framework can also be used to address the “pacing problem,” where different actors adapt at different rates to innovations.

To help ensure transparency and accountability when managing and monitoring environmental quality in today’s big data setting, the authors developed “a new ecosystem of drivers” graphic to help illustrate this new paradigm (see Figure). The graphic’s four quadrants show the actors and structural organization of drivers. The Comment dives into detail about how the framework provides a starting point for questions, such as how to ensure that legal systems can anticipate manipulation of data, or how citizen-generated data can be used to improve environmental quality. For example, it could be used to examine how citizen-collected data offers amends to the Clean Water Act. The framework can also be used to address the “pacing problem,” where different actors adapt at different rates to innovations.

As Fulton and Rejeski describe, a new environmental paradigm will “require an experimental mind-set, perhaps running many small experiments, failing fast if needed, and learning from failure,” and the new framework could take “an agile and adaptive development approach done with partners in both the public and private sectors.” In the end, however, the new paradigm will require a changing structure in leadership: “It is unclear who will take this on but it might be the biggest challenge of all in shaping our environmental future.”

ELI is making this featured News & Analysis article available free for download. To access all that ELR has to offer, including the full content of News & Analysis and its archive, you must have a subscription.

To learn more, visit www.elr.info.