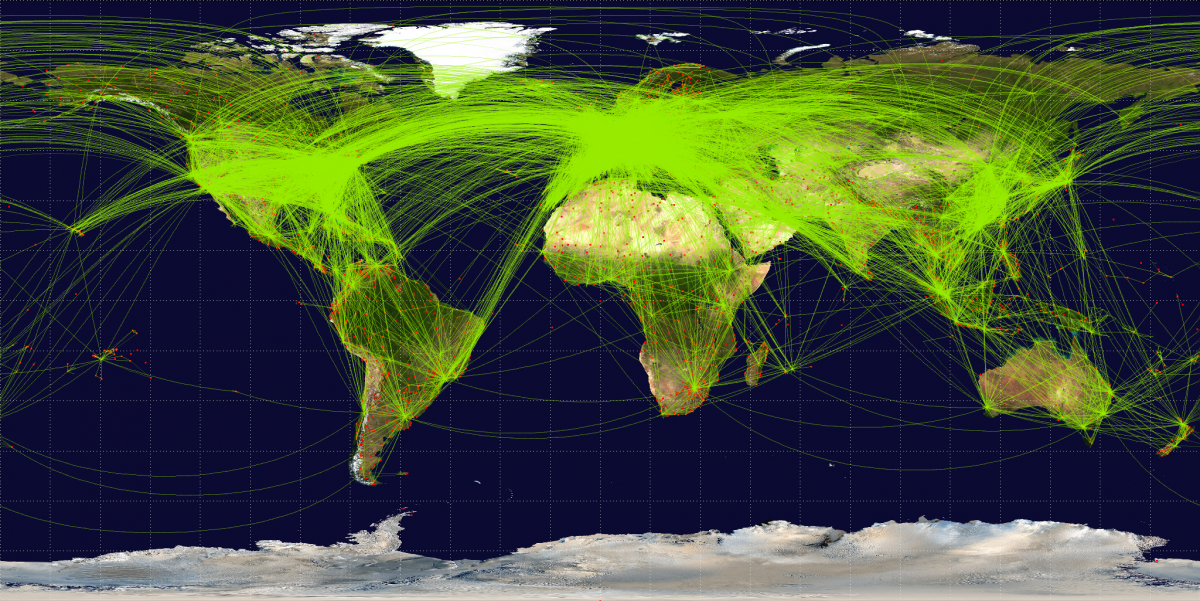

Rising levels of global consumption are having significant impacts on biodiversity worldwide. The world is facing its sixth extinction, a massive loss of biodiversity, with extinctions occurring at 100-1,000 times pre-human levels. International trade increases these threats. A Nature article documenting the impacts of trade in thousands of commodity chains concluded that 30% of threats to threatened and endangered species globally were due to international trade. It found that while wealthy countries drive most consumption, the greatest threats to species are found further down the supply chain, in the developing countries that produce the commodities sought after by the richer nations.

Including effective environmental provisions in trade agreements can potentially provide a much-needed counterbalance to the environmental impacts of increased trade. In a free trade agreement, environmental provisions could provide an additional enforcement tool to ensure compliance with international environmental standards. They can also help protect the right of a country to implement environmental regulation. Less widely discussed, environmental provisions could also help level the regulatory playing field for U.S. companies competing in a global marketplace. At “Issues for the New Administration: Trade and the Environment,” an event held at ELI and co-sponsored by the D.C. Bar, ABA SEER, and ELI, panelist members of the Trade and Environment Policy Advisory Committee (TEPAC) discussed these and other issues.

With the administration’s new focus on renegotiating NAFTA and potentially other trade agreements, it is critical that impacts to the environment be understood and considered in the discussions. Although now rejected, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) may provide lessons for moving forward. The TPP’s Environment Chapter contained several provisions illustrating how impacts on fisheries, biological diversity, and illegal wildlife may be addressed in future international trade agreements. Environmental concerns are evidently reflected in Congress’ thinking on international trade: last month, House Democrats put forth a resolution asking President Trump to include “strong, binding, and enforceable . . . environmental standards” that include the ability to tax imports “made under highly climate-polluting conditions” in the trade agreement that would replace NAFTA.

|

Congress’ overall negotiating objectives with regard to the TPP and the environment included requirements that the parties comply with multilateral environmental agreements to which they are already a party; not derogate from their own environmental laws; and enforce their own environmental laws while allowing for prosecutorial discretion. These objectives can be seen throughout the TPP’s various environmental provisions. For example, each party would have been required to “adopt, maintain and implement laws, regulations and any other measures to fulfil its obligations under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).” (Article 20.17). With respect to marine fisheries, parties were to “seek to operate a fisheries management system” that followed standards set forth in certain international fisheries instruments. (Article 20.16). TPP parties that had not signed the fisheries agreements were required to seek to follow these standards nonetheless. Subsidies to fishing vessels operating illegally or fishing overfished stocks were specifically prohibited. (Article 20.16). And parties were disallowed from failing to “effectively enforce [their] environmental laws,” though they would have prosecutorial discretion in that regard. (Article 20.3).

Other environmental provisions contained in the TPP sought to protect U.S. industry and level the regulatory playing field, while simultaneously protecting the environment. For starters, the agreement’s elimination of tariffs on environmental goods and services (Article 20.18) would benefit the growing U.S. environmental sector, whose exports were valued at $106 billion in 2013. Another provision required parties to “take measures to combat” the trade of wild species that were taken in violation of the party’s or another party’s law. (Article 20.17). This provision was aimed at reducing illegal trade, which unfairly competes with U.S. production. Another provision provided that parties could not weaken environmental laws to increase trade or investment. (Article 20.3).

Regardless of which provisions are included in a future trade agreement, the language must be specific and mandatory in order to promote effective enforcement. Including specific and enforceable environmental provisions in trade agreements is important for both improving environmental protection globally and providing a more predictable and level regulatory environment. It is helpful to tie environmental provisions directly to the requirements of other environmental agreements. In addition, the agreement must be looked at holistically so that other provisions of the agreement do not undermine the environmental commitments (stay tuned for a subsequent blog on this issue).

As the Nature article made clear, the demand for goods results in impacts further down the supply chain, making it too easy for impacts to be unseen or misunderstood. When new or revised trade agreements are negotiated, environmental provisions must therefore be a central concern.