Vibrant Environment

All | Biodiversity | Climate Change and Sustainability | Environmental Justice | Governance and Rule of Law | Land Use and Natural Resources | Oceans and Coasts | Pollution Control

As we celebrate National Wetlands Month in May, one of the Washington State Department of Ecology’s best and brightest—and a longtime “hero” of Washington State’s wetlands—Lauren Driscoll has been recognized for her lifetime of wetlands program development work by ELI.

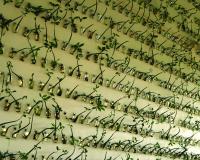

I was introduced to mangroves early in my childhood during family trips to Bear Cut in Key Biscayne, Florida—the same plants that grew in my family’s hometown on the northern coast of Cuba. In 2003, I first used mangrove imagery in my artwork as a metaphor for the immigrant. I imagined the mangrove propagules floating along the water and setting root on a sandbar. Little by little they would grow alongside each other, capture sediment, create land, and build new habitats. Like immigrants in a community who come together to support one another, the roots of each mangrove tree come together to create a formidable structure that protects against the dangers of storm surge.

The coronavirus pandemic has focused increased attention on indoor air quality and ventilation. Yet, many people remain unaware of the health risks posed by an activity that occurs every day in their homes: cooking.

Climate change and environmental degradation not only pose visible threats to the well-being of millions today, but also present hazards to future generations—challenging the principle of intergenerational equity. Intergenerational equity, a concept that calls for fairness and justice between generations, requires that past, present, and future generations share the Earth’s resources in a fair and equitable manner. Related to this is the concept of intergenerational well-being, which calls on present generations to live and govern in a way that will allow future generations to live healthy and complete lives.

Part One of this blog series discussed interstate electricity transmission as an integral part of grid resilience through a California and Western EIM case study. Part Two builds on this background by evaluating the regulatory framework that underpins the division of transmission siting authority and analyzing its legal implications.

Last August, over half a million California residents simultaneously lost power during the state’s first rolling blackout in 20 years. Critics of renewable energy have pointed to California’s recent gains in wind and solar power penetration to argue that the large-scale outage suggests a correlation between increased variable renewable energy and increased grid vulnerabilities. Meanwhile, in an analysis released in January, CAISO, California’s energy market operator, attributed the large-scale outage to a climate change-induced heat wave, which led electricity demand to exceed existing resource adequacy. In the same report, CAISO proposes “consideration of transmission build out” to overcome transmission constraints across multiple interstate electricity lines as a key to preventing future outages. Whether and how to move electrons across state borders, however, has been at the center of California’s energy transition debate for years.

In “Measuring the NEPA Litigation Burden: A Review of 1,499 Federal Court Cases,” Prof. John C. Ruple and Kayla M. Race quantitatively demonstrate that the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) compliance and litigation burdens may be overstated—findings they argue should inform any revisions to NEPA. The article was originally published in Lewis & Clark Law School’s Environmental Law in 2020. The piece was also selected as a top 20 article for the Environmental Law and Policy Annual Review in 2020, an ELI-Vanderbilt Law School project that identifies innovative environmental law and policy proposals each year.

Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Zika, Yellow Fever—what do all these diseases have in common? They are caused by viruses that enter human bloodstreams via mosquito bites. The culprit that transmits these viruses is the Aedes aegypti mosquito. On April 26, Wiley Rein LLP client Oxitec, Ltd.

Food waste is a systemwide problem, affecting all stages of the supply chain. Therefore, solving it will take a systemwide approach. A new report by ReFED, Roadmap to 2030: Reducing U.S. Food Waste by 50%, was designed to provide food businesses, governments, funders, and more with a framework to align their food waste reduction efforts.

This past March, ELI wrapped up its 17th Annual Western Boot Camp on Environmental Law. With a record-breaking 86 participants, this year’s virtual event brought together legal experts and attorneys for three days to explore in-depth issues in U.S. environmental law and policy.