Strategies for cities and states to reduce food waste can be thought of through the lens of the “Three Rs” of EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy—reduction, reuse, and recycling. In food waste terms, the Three Rs mean preventing wasted food at the source, donating wasted food leftovers, and recycling food waste through composting or anaerobic digestion.

The recent ReFED report on reducing food waste quantifies the economic value and diversion potential of different strategies related to each of the Three Rs. According to ReFED, source reduction and donation generate the most economic value per ton of food saved, while food recycling and composting have the potential to divert a much greater quantity of food from landfills.

The upshot for cities and states is that effective food waste reduction policies should encompass all three types of strategies. Moreover, while the Three Rs are often presented as distinct and parallel approaches, in fact, they share significant feedbacks and linkages. For example, a business owner who begins sorting out food scraps for composting may realize how much food is wasted, motivating her to donate more leftovers.

|

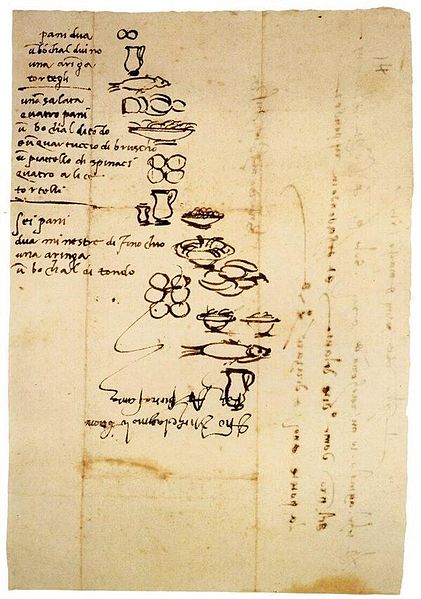

In this post, we focus on source reduction; subsequent blogs will cover the donation of surplus food and recycling of scraps. “Source reduction” strategies seek to reduce the amount of food waste generated in the first place by, for example, strategic planning of meals or menu items, purchasing only the ingredients needed for a dish and reducing portion sizes to avoid plate waste.

The role of cities and states is to encourage waste generators to employ these strategies. As such, policymakers should first consider where waste occurs—and why. ReFED estimates that 40% of food waste occurs in consumer-facing businesses, while 43% occurs in households, compared with 16% on farms and 2% in manufacturing facilities.

Though businesses and households waste similar amounts of food in aggregate, they do so for different reasons. Significant drivers of food waste in businesses include customers’ high expectations of variety and freshness of ingredients. ReFED notes that food waste in households can occur for the same reasons but also as a result of efforts to provide ample food for family and guests; misunderstood date labels; poor food storage and repurposing practices; and failure to plan grocery purchases.

In light of the varied challenges faced across sectors and jurisdictions, local governments may choose different starting points for source reduction. Some cities, such as Boulder, Colorado, may opt to start by conducting a waste stream assessment to establish a baseline for food waste reductions. A different approach, exemplified by Austin, Texas, is to lead by example through a commitment to reduce waste from public agencies.

Another tactic is to start by setting waste reduction goals. In 2016, the U.S. Conference of Mayors passed a resolution adopting the federal goal of 50% reduction in food loss and waste by 2030, encouraging cities to “facilitate the adoption of new food waste reduction innovations through pilot projects, public-private partnerships and municipal procurement preferences.”

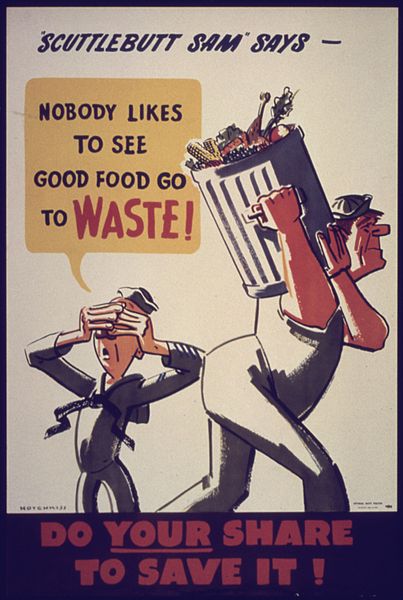

Whether or not cities begin by setting goals, they have a range of food waste reduction strategies to pick from that fall along a spectrum ranging from education and technical support to regulation. Beginning with the least restrictive policies, cities and states can build a culture of waste awareness and reduction by sharing educational resources such as the Ad Council’s Save the Food and EPA’s Food: Too Good to Waste campaigns. The Center for Food Loss and Waste Solutions assembles these awareness materials, along with other resources for citizens businesses, and government, at its Further With Food website.

Local governments can target households, specifically, by providing information resources tailored to better planning of meals, storage of food, and reuse of leftovers in new dishes. The Food Keeper App is one such resource, which provides detailed guidance on how long different foods can be stored, and in which conditions. Cities can likewise publicize resources that are available for purchase on popular websites, such as Dana Gunders’ Waste-Free Kitchen Handbook, which includes an array of recipes designed to use up odds and ends frequently left in the refrigerator.

Cities and states can similarly play an important role in helping businesses identify waste reduction strategies. Massachusetts’ Recycling Works program offers an array of practical resources, including tips for waste reduction, technical assistance for starting programs, and searchable databases of haulers and recycling processors. Recycling Works also provides businesses a phone number and e-mail address to contact the Department of Health directly for real-time guidance.

One way for local governments to engage the commercial sector directly is by recognizing businesses for voluntary food waste reduction efforts. In 2013, New York City challenged restaurants to reduce food waste by 50% or more in exchange for technical assistance and public recognition for their efforts. After six months, over 100 participating businesses collectively diverted more than 2,500 tons of food waste. The mayor of Nashville, Tennessee, recently announced a Food Saver Challenge program for restaurants that will be launched soon.

|

To complement such challenges, cities and states can provide practical tools for waste tracking. Software programs such as LeanPath help large-scale foodservice providers identify sources of waste, measure its volume, and quantify its value. By subsidizing the use of LeanPath for U.C. Berkeley, Alameda County, California, helped the university reduce its annual food waste by 19%, equaling 27 tons of food worth over $98,000. Boulder, Colorado, takes a similar approach by sponsoring third-party organizations to conduct waste audits and help businesses identify opportunities for waste reduction.

A stronger approach to source reduction might entail leveraging fees for waste management services. Unit-based or “pay-as-you-throw” pricing for waste hauling services provides incentives for generators—whether household or commercial—to reduce solid waste. When communities with unit-based pricing further mandate source separation of food waste, generators confront just how much food they waste, and how much it costs them in solid waste fees. This strategy has been used effectively in Seattle and San Francisco.

A combination of these approaches may ultimately lay the foundation for cities and states to ban food waste from landfills or mandate food waste recycling. Commercial organics recycling mandates have taken effect statewide in California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, and on the local level in New York City and Austin. Some jurisdictions, such as San Francisco and the state of Vermont, have expanded these requirements to cover residential as well as commercial food waste generators.

Altogether, source reduction is an important component of any city or state food waste reduction strategy. However, the strategies highlighted here will be most successful when integrated with the other two Rs: reuse and recycling. We turn to these next.

Carol, Linda, and Emmett work on the Food Waste Initiative at ELI. Other blogs in the ELI food waste series can be found here.